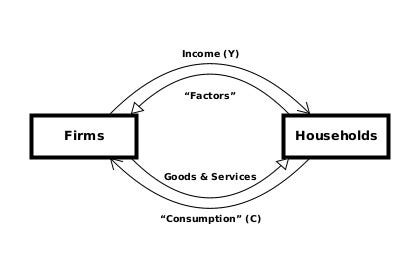

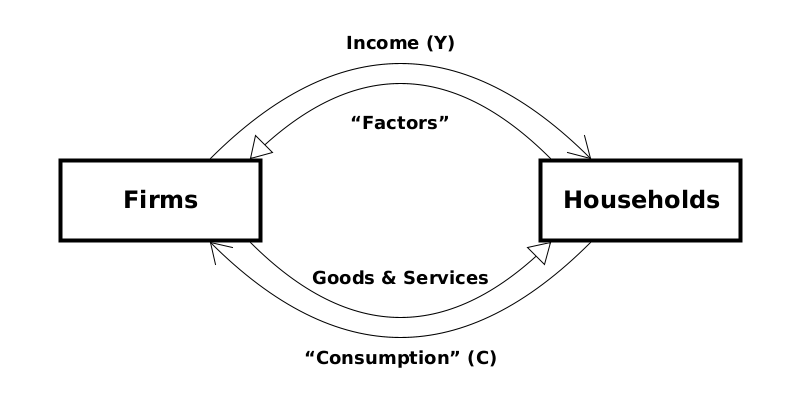

A “circular flow of income” model is a way of thinking about the whole economy at once (i.e. macroeconomics). It groups people1 into sectors (e.g. firms, households, government), and looks at the movement of money between different sectors, with a special focus on these transfers:

From firms to households — paying for “factors”2 (wages to workers, dividends to owners, etc.); and

From households to firms — consumers paying for the goods and services which the firms produce.

This flow of money (the arrows with plain heads) back and forth between firms and households is described as a “circular flow”, like an electric circuit or a central heating system. Economists often use these models to help them to think about how the economy works, to draw conclusions, and to make policy recommendations to governments and central banks.

In a short series, we’ll look at some circular flow models, and use the One Lesson to see why the conclusions economists draw can be seriously wrong, potentially making the recommendations extremely harmful.

Why do economists model the economy this way?

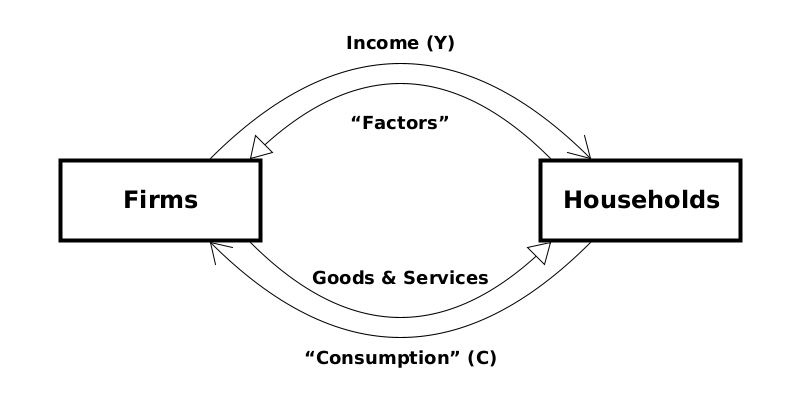

In the One Lesson, the simplest type of economic activity is the action, represented by an arrow. It increases one person’s raw net worth3, and decreases another person’s by exactly the same amount. As we’ve seen in the series on macroeconomics, this lets us group all economic activity into simple chains or loops, according to which tangible asset or debt is involved in the transfer. And the whole economy can be understood as the “superposition”4 of all of these chains and loops.

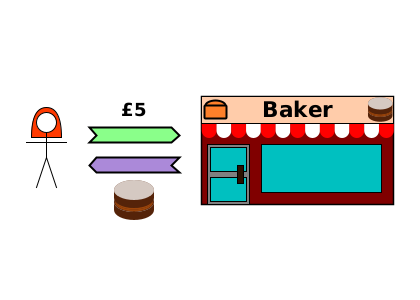

But most economists think of the more complex transaction as the basic element from which all economic activity is composed.

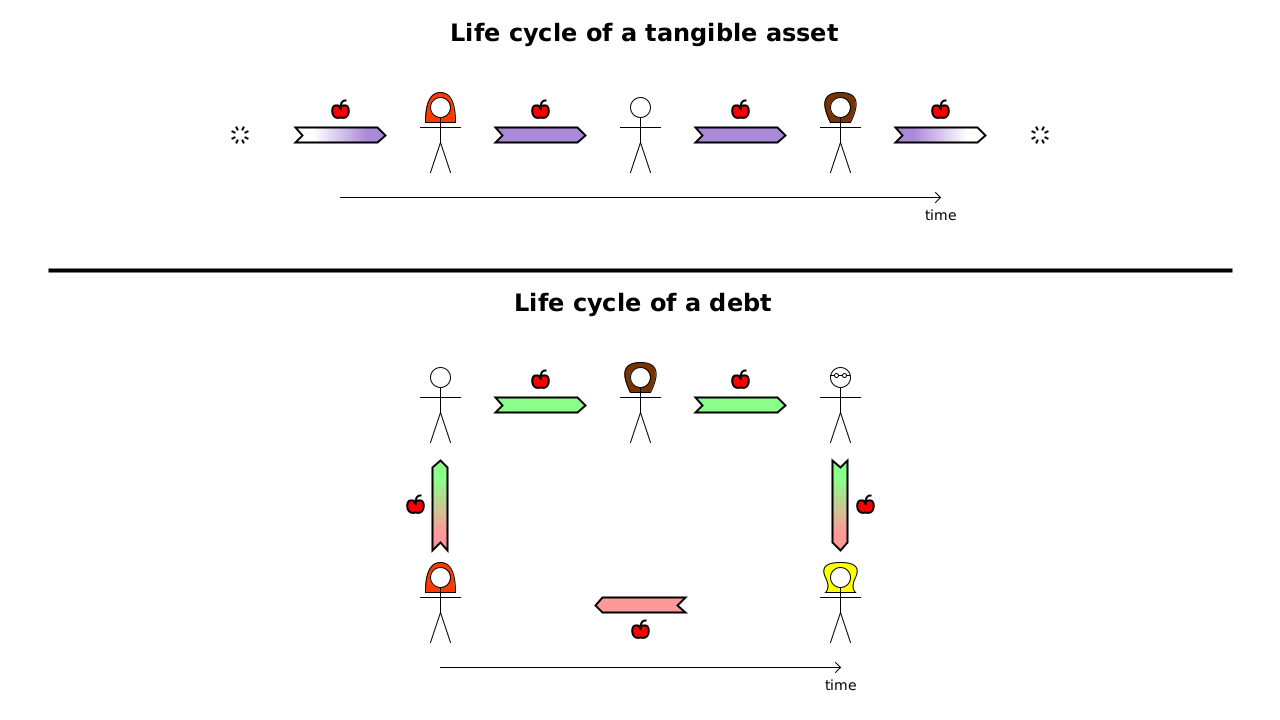

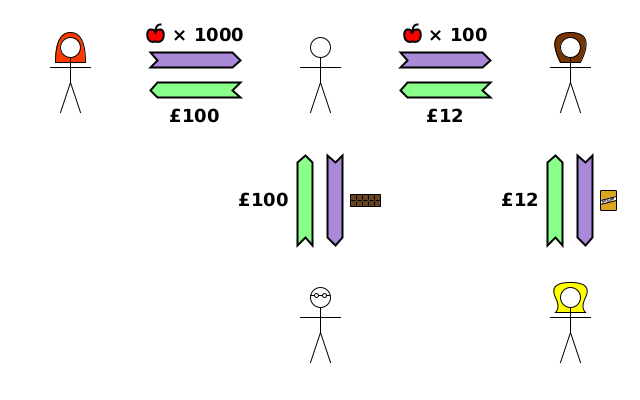

It’s difficult to group related transactions together because each transaction involves two (or more) goods, services or debts. It’s like the six degrees of separation idea: almost any two transactions are related to each other in some way. For example, if Alice sells 1,000 apples to Bob (a wholesaler), and Bob sells 100 of them to Charlotte (who has a shop), it’s likely that different money was used for the two transactions.

Here, the £12 Charlotte spent came from selling sugar, and the £100 Bob spent came from selling chocolate to Dom’s restaurant. But there’s no meaningful connection between those particular apples, sugar and chocolate.

Because transactions can’t usefully be put into separate groups based on what was exchanged, economists usually take a different approach, grouping them according to the time period (usually a year) when they happened, the nation in which they took place, and the sectors involved in the transaction.

There’s nothing wrong with grouping transactions in this way, but it’s very easy to draw wrong conclusions — especially if you make wrong assumptions, don’t think about how the model relates to the real world, have an unhealthy obsession with money, or forget that one year’s transactions can affect which transactions occur in later years. Unfortunately, these mistakes are often made.

The 2-sector model

Let’s start with the simplest circular flow model, with only 2 sectors: firms and households. The “people” who produce goods and services to be sold are placed into a group called “firms”. Everyone else is placed into the “households” sector. There are a couple of important assumptions:

There’s a fixed amount of money.

If firms make a profit, they immediately pay it as a dividend to the shareholders (in the households sector).

While the assumptions are unrealistic, it’s often a good idea to start with a simpler model, to try to understand that, and then to begin introducing more realistic assumptions to make better models. The trick is making sure that you actually do understand the simpler model before moving on.

So, firms pay households for factors e.g. wages (for their labour) and dividends (profits). And households pay firms for their goods and services.

Payment for factors is known as (household) income, and represented with the letter ‘Y’5.

Spending on goods and services is known as consumption6, and represented with the letter ‘C’.

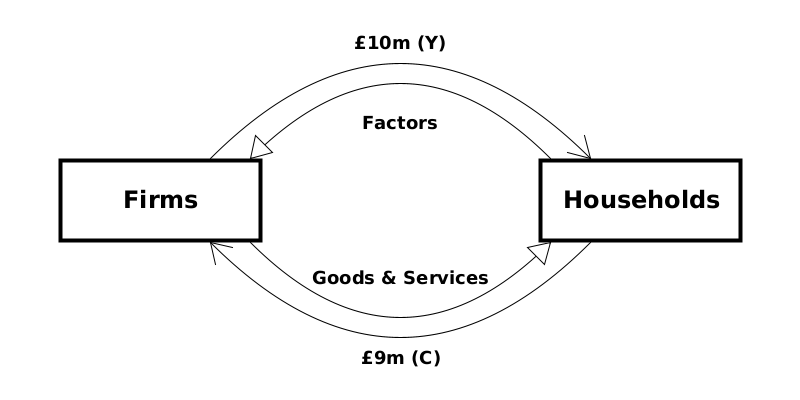

Many economists would argue that Y must be equal to C, because otherwise one side or the other will run out of money. But is that right?

The answer is: no. Not even in this simple model with a fixed amount of money, and without any lending from households to firms. This is an example where it’s important to check our understanding by relating the model to the real world.

Suppose in year 1, Y = £10m, and C = £9m. That is, households have been paid £10m, but only spent £9m on goods and services. Firms have lost £1m of money. Is this a problem?

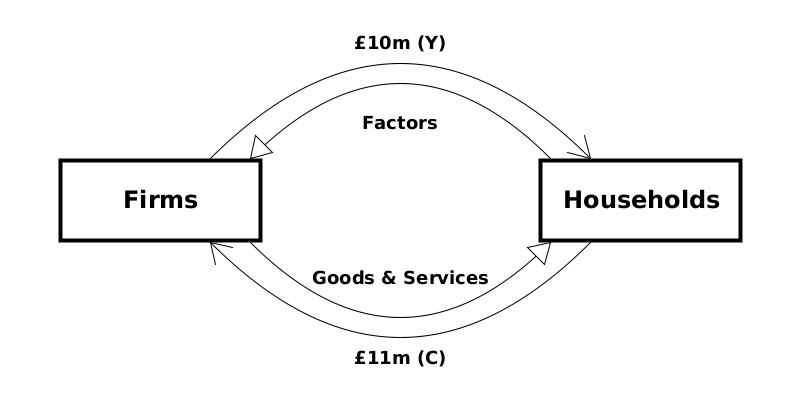

Well, if firms started the year with £2m, then no, it isn’t a problem at all — certainly not for that year, because they still have £1m left. Obviously this situation can’t be repeated forever, because the firms will eventually run out of money. But just imagine that the firms have been so productive in year 1 that they end the year with lots of goods in their warehouses, which they can sell for £1m the following year. So in year 2, we could have Y = £10m, and C = £11m (households buy all the goods and services produced in year 2 plus the goods left unsold at the end of year 1). Then the two sectors end up with the same amount of money they had at the beginning of year 1.

This 2-year cycle could repeat forever, first with a net flow from firms to households, and then a net flow from households to firms later on. As long as neither side runs out of money, this back-and-forth is just as sustainable as the simpler case of households spending all of their income immediately.

Summary

Economists generally treat transactions (rather than individual actions) as the smallest unit of activity. This leads them to analyse the economy by grouping people into sectors, and looking at the flows of money between those sectors, to see what they can learn from this. In particular, they look at the circular flow of money back and forth between firms and households.

But sometimes they can make mistakes. Even in a very simple model with just these two sectors, economists often conclude incorrectly that the system can only be stable if households spend all of their income. But as we’ve seen, as long as people have enough money to start with, it’s possible for the system to be just as stable with flows first mostly in one direction, and then mostly back in the other direction. And we haven’t even considered borrowing yet.

As usual, “people” here refers to both real people and corporate legal entities, such as limited companies and governments.

Factors are resources needed to produce things, usually categorised as land (a plot of land, or raw materials extracted from it), labour (physical or intellectual work) and capital (buildings, tools and machinery).

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

Superposition is where you can break a complex problem into smaller, simpler parts, work out a solution for each of the parts, and get the solution to the whole problem by simply adding up the solutions to the parts.

You might think ‘I’ would represent income, but that’s used to represent investment.

Consumption is a really bad name for it, because buying something and consuming it are very different. A fridge or vacuum cleaner isn’t normally consumed until years after it was bought. A well-built house might not be consumed for centuries.