We’ve looked at a 2-sector circular flow model, both the traditional one (which doesn’t explicitly show production or consumption), and a One Lesson version (which does, and where the meaning of the arrows is clear and precise).

What effect does adding a banking sector have?

(TL;DR: it shows how firms can continue operating even if they continually spend more money on factors than they receive when they sell goods and services. The usual 3-sector model from the textbooks also makes some important errors, and causes pointless arguments between people of different economic schools over whether setting interest rates to the “correct” level is enough to prevent firms running out of money).

The 3-sector story

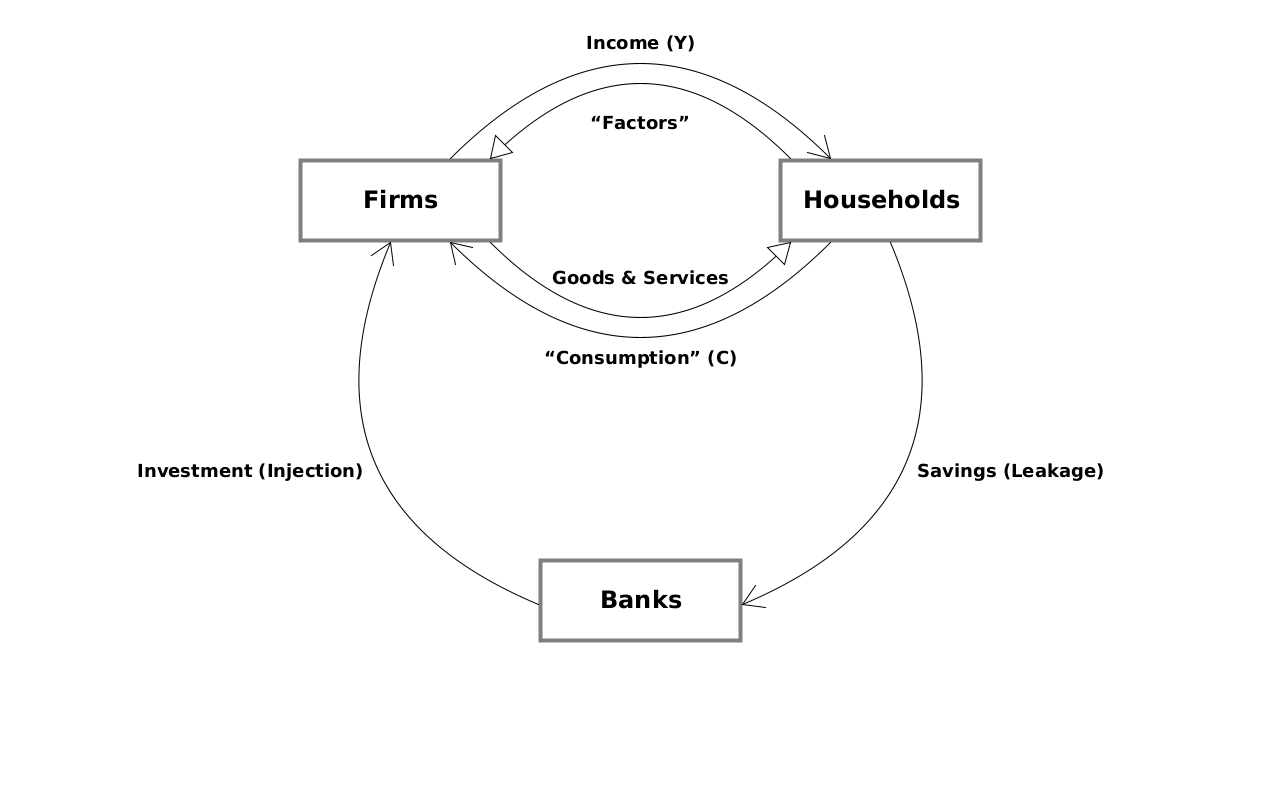

Here’s a (common, but bad) 3-sector circular flow model:

Notice that the top half is the same as the 2-sector model. The additions are:

There’s a new sector (“Banks”)

There’s a flow of money (“Savings”) from households to banks.

There’s a flow of money (“Investment”) from banks to firms.

Before reading on, spend a minute looking at the interactions between banks and the other sectors, and see if you notice anything odd about it compared to the circular flow between firms and households.

Here’s the sort of (bad) story which a typical economics textbook tells about this (bad) model:

As with the 2-sector model, firms pay households for factors, and households pay firms for the goods and services they produce. There is a circular flow of money between firms and households. But households save some of their income by depositing it in banks. This is a “leakage” from the circular flow, meaning that some money transferred from firms to households doesn’t make it back to the firms. Unless something is done, the firms will eventually run out of money.

Firms can offset the effect of the leakage by borrowing from banks for investment (perhaps to buy machinery or build a new factory). This is an “injection” of money back into the circular flow. As long as investment is equal to savings, the circular flow can continue. But if investment is less than savings, firms will eventually run out of money.

There are two main competing theories about how to make investment lending keep up with household savings. Neoclassical1 economists say that this happens by banks adjusting the interest rates which they charge firms for loans and which they pay to savers: if investment is less than saving, banks can reduce the interest rate, encouraging households to save less (and spend more) and firms to borrow more. Keynesian2 economists say that this isn’t always enough, and that government intervention is sometimes necessary e.g. deficit spending.

Analysis

There are so many problems with this model and narrative that it’s hard to choose a good place to begin.

Let’s start with the diagram itself. Did you spot anything odd about the interactions between the banks and the other sectors? Compare it to the circular flow: when firms transfer money to households, they get factors in exchange. And when households transfer money to firms, they get goods and services in exchange.

What do households get in exchange when they transfer money (savings) to the banks? And what do banks get in exchange when they transfer money (investment loans) to firms? According to the model… nothing!

So in this model, which is supposed to approximate the real world, household savings are essentially a donation from households to banks, and investment loans are a donation from banks to firms! Where are the withdrawals of savings by households? Where are the loan repayments by firms?

While it’s ok to make simplifications in an economic model (e.g. seeing how the economy would work without banks at all), because it can help you to understand a simpler problem first, it’s worse than useless to introduce only half of a new concept. Including banks, but ignoring half of their interactions with the rest of the economy, is absolutely absurd.

You may have heard the expression “garbage-in-garbage-out”, sometimes abbreviated GIGO. That’s relevant here. If your model treats banks as a means of transferring money indirectly from households to firms, with nothing given in return, any conclusions you draw from the model will be at best irrelevant to the real world. But it’s likely to be far worse than irrelevant: it will probably encourage the policy makers’ advisors to come up with recommendations which don’t make any sense in the real world in which money also flows from firms to banks, and from banks to households.

Given this fatal flaw, it seems unnecessary to find more faults with it, but I think it deserves it. So here are some more:

Assumes equilibrium. We’ve already seen in the discussion of the 2-sector circular flow model that the idea that household income has to equal household spending on goods and services is wrong. Even if there’s a fixed amount of money in the economy, and no banks or lending, there can, for example, be a net flow in one direction in one year and a net flow in the other direction the following year. As long as nobody runs out of money, it simply isn’t a problem.

Ignores built-in reversal of leakages/injections. Each time households deposit some of their income at the bank, the bank’s debt to households increases. And each time banks lend to firms, the firms’ debt to banks increases. Unless these debts are never paid (in which case they were donations after all), the “savings” leakage eventually leads to an equal “withdrawal” injection, and an “investment” injection eventually leads to an equal “repayment” leakage. So the savings leakage and the investment injection are automatically cancelled out by the reverse action, at least in the long term. They don’t need to be made to equal to each other. The arguments between different schools of economics (Neoclassical vs Keynesian) about how to make investment equal to savings are completely missing the point.

Assumes investment ≤ savings. For some reason, the case where investment > savings isn’t considered. I can only guess that this is because there’s an assumption that the money being lent to firms must have been saved by households in the same year, and the bank can’t lend what it doesn’t have. But (i) money deposited in earlier years, but not yet lent, would allow banks to lend more than this year’s savings, and (ii) it’s irrelevant anyway because banks create money when they make loans: they’re not relying on savers depositing money first.

Summary

All in all, the standard 3-sector circular flow model (firms, households and banks) is badly flawed, most obviously because it includes household saving and investment lending to firms, but doesn’t include household withdrawals or loan repayments by firms. Any conclusions drawn from it are therefore likely to be completely wrong.

We’ll see how the One Lesson can salvage the situation in an upcoming post.

Neoclassical economics is the approach taught at the majority of universities.

This is the distant second approach taught at universities, following the ideas of John Maynard Keynes.