If banks charge interest on loans, it seems like it takes money out of the circular flow between firms and households. Does that cause the money to drain out of the economy and bring economic stagnation?

(TL;DR: No).

Let’s see how we can add banks charging interest to the 3-sector circular flow model (firms, households and banks).

It’s actually pretty easy. While we’re at it, we’ll add in borrowers defaulting and employees being paid wages too, because those are the main reasons that banks have to charge interest.

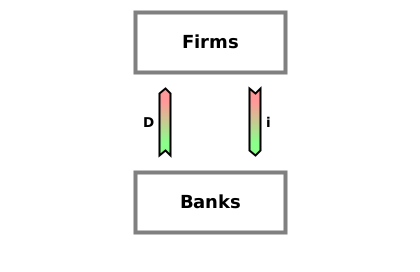

As a reminder, here’s the original 3-sector diagram:

With that first attempt at a 3-sector model (which has no defaults, no interest and no transfers from banks to households), we can see by looking at the arrows pointing towards and away from banks that their raw net worth1 never changes: the amount of new lending to firms, I, in the time period which the diagram shows is exactly matched by the amount which firms promise to pay back as a result, and the amount of repayment by firms, R, in the time period is exactly matched by the amount which the banks write off from the outstanding loans.

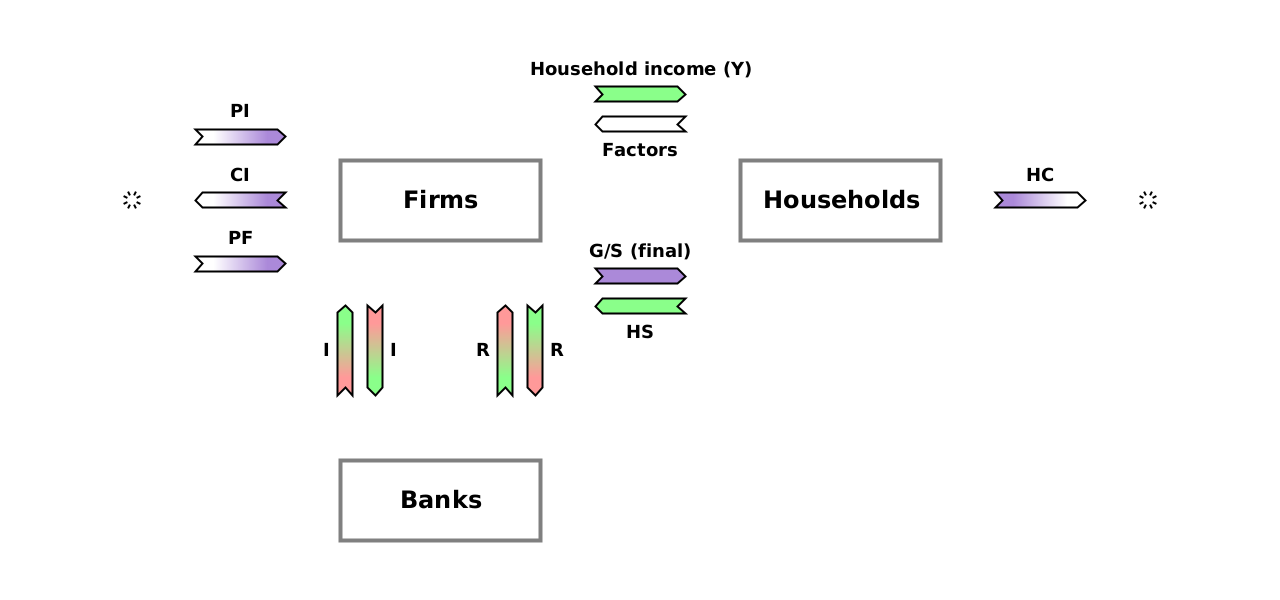

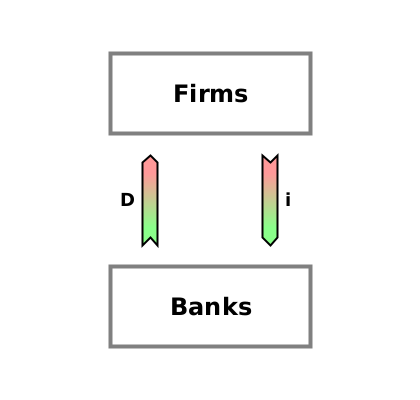

But this is unrealistic. Firms sometimes do default, and this happens, the bank has to write it off, which decreases the bank’s RNW (and increases the firm’s by the same amount2). Let’s use D to represent the total amount of all defaults in the time which the diagram shows.

Unless a bank has some income, ongoing defaults will cause its RNW to keep decreasing, eventually making it insolvent. That’s one major reason why banks generally charge interest. (Unless they are subsidised by someone, the only alternative is charging fees for their services). Let’s use i to mean the total amount of interest charged over the time period of the diagram.

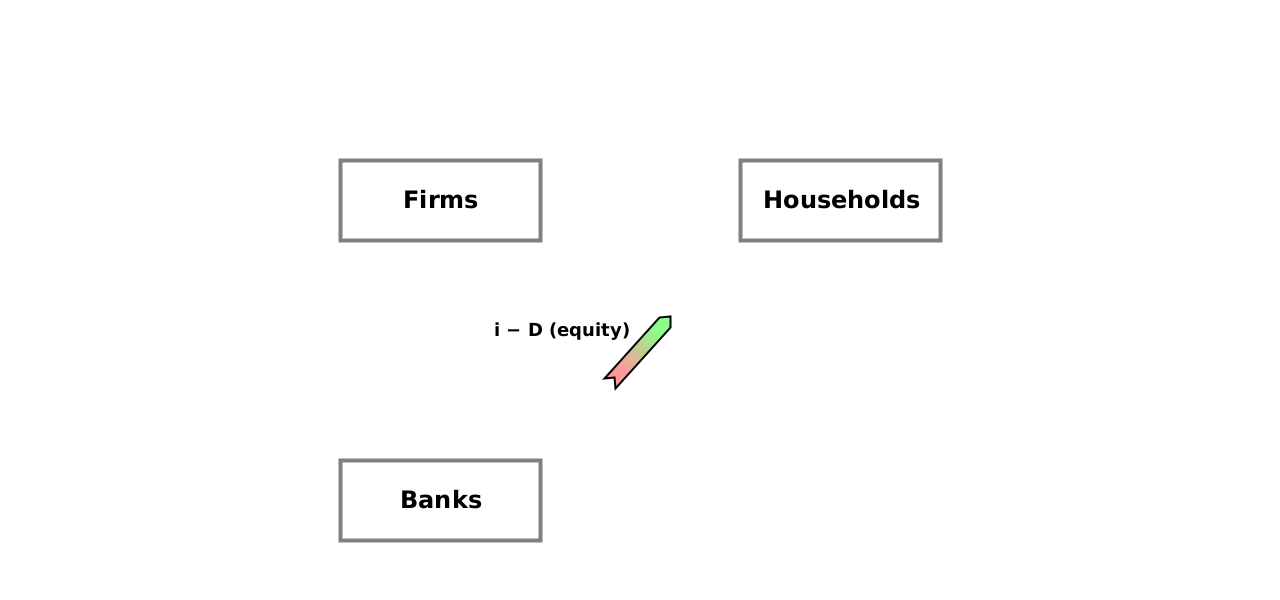

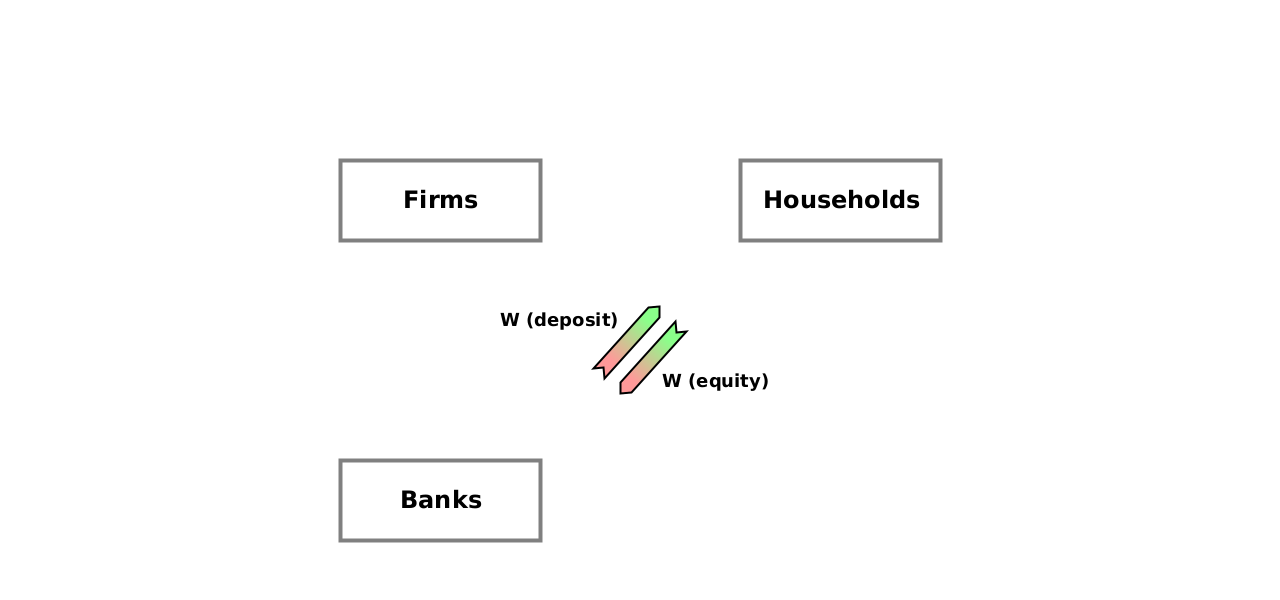

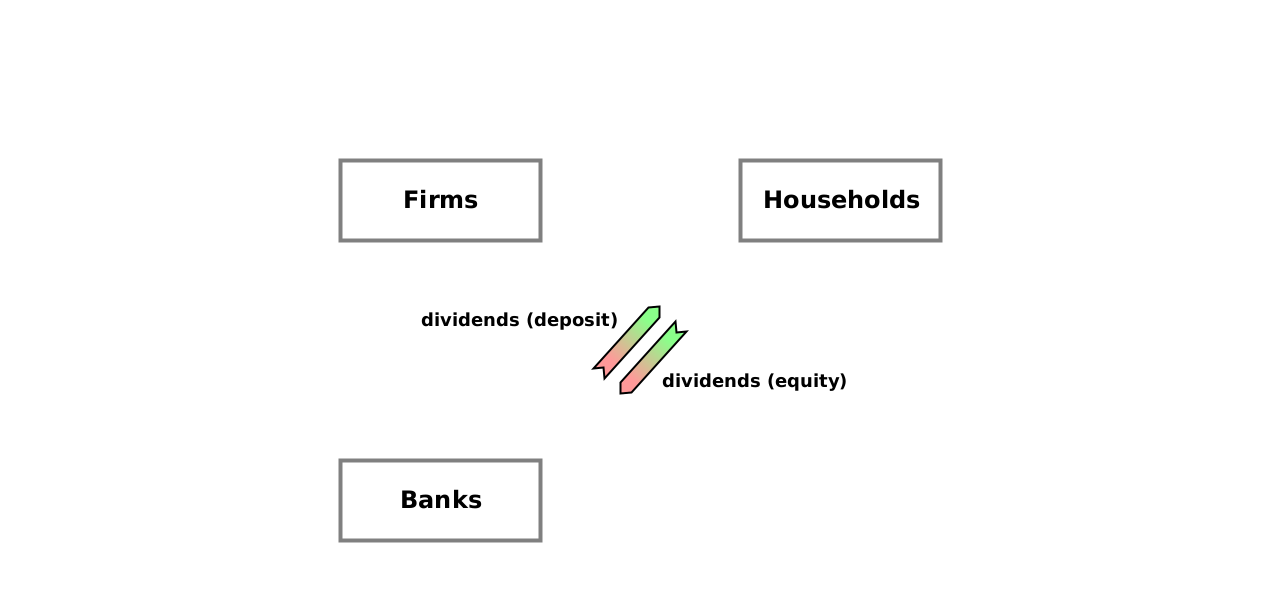

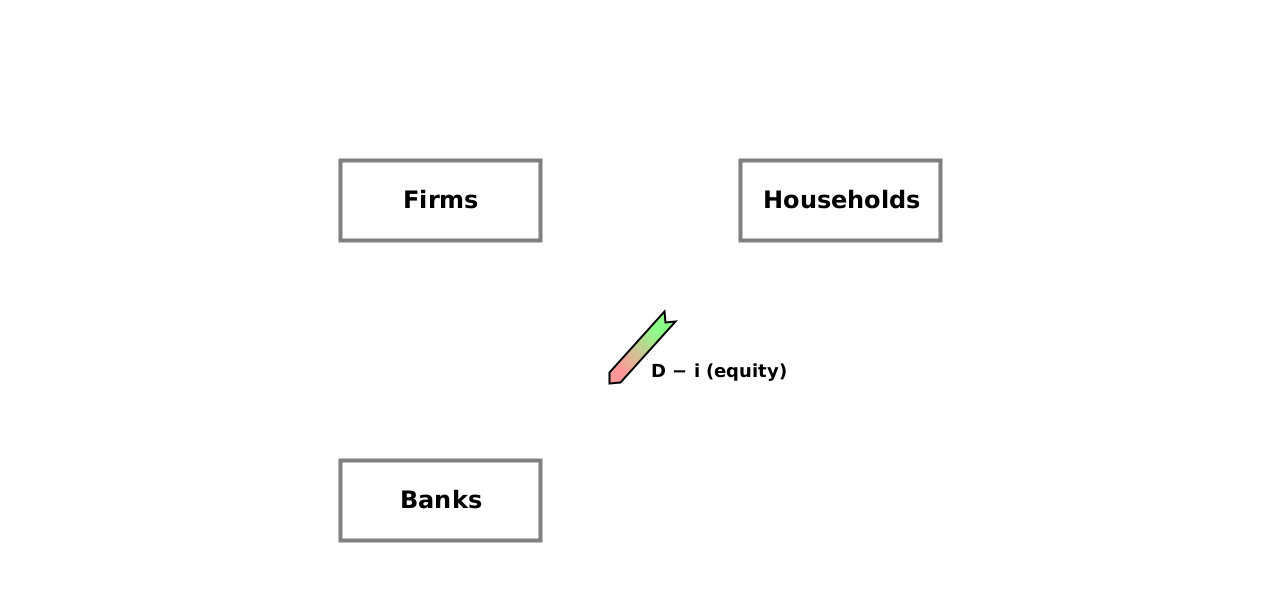

It’s time to update the diagram, but instead of showing the whole thing, which would be very cluttered, let’s just show the parts we’ve added.

Charged interest is a new debt owed by the firm to the bank. (It’s then settled in the same way as repaying the original loan — by the firm writing off some of its account balance in exchange for the bank writing off an equal amount owed by the firm to it. To avoid adding extra arrows, let’s just say that the two R arrows in the original diagram include these payments of interest after they’ve been charged).

So in any time period, defaults and the charging of interest cause firms’ and banks’ RNWs to change by the following amounts:

i and D are generally measured in the local currency units, so they can be compared. If i > D, the banks’ combined RNW has increased from the opposing effects of charging interest and writing off defaults. If i < D, banks’ combined RNW has decreased. Let’s look at both cases:

i > D

Because the banks received more in interest than they lost from defaults, the effect is that banks’ combined RNW has increased by i - D, and so their combined equity also increases by i - D to compensate. This is a form of household income, because it increases the RNW of the shareholders as we saw in the post about equity vs net worth.

What we haven’t looked at yet is paying employees for their work. But it turns out that this doesn’t affect household income. When a bank pays its employees’ wages, this decreases the bank’s RNW and increases the employees’ RNWs — this is household income for the employees. But it also means that the bank’s equity decreases by the amount of the wages paid, which is negative household income for the shareholders.

So no matter how much is paid in wages, the contribution to household income from banks is still i - D. We can call this YB3. Since households are getting some of their income from banks now, it would be wrong to call the payments from firms to households “household income”. So we’ll call the contribution to household income from firms YF. And total household income, Y, is these two added together:

Y = YF + YB

A bank pays wages to its employees simply by creating a deposit for them — increasing the balance in their accounts. Similarly, if at some point it pays a dividend to its shareholders because it decides it doesn’t want so much equity, it again does this by creating a deposit for them.

Notice that a bank doesn’t have to lend in order to create deposits (bank money) for someone. In accounting terms, it just credits their account (and debits equity), which it’s completely free to do as long as it has enough equity.

i < D

Because the combination of interest and defaults has caused the banks’ combined RNW to decrease by D - i, their combined equity decreases by D - i to compensate. You can either think of this as negative household income or household expenditure with no goods or services received in return.

Employees still have to be paid, but just like above, this household income for them is negative household income for the shareholders, so they cancel each other out, and total household income from banks is the negative amount i - D.

Summary

The charging of interest on loans is a leakage from the circular flow between firms and households, in that the RNW transferred from firms to banks doesn’t go back from firms to households. But it’s also an equal injection into the circular flow, in that it is transferred from banks to households who are employees or shareholders of the banks.

Defaults work in the opposite direction: they are a leakage because RNW is transferred from households to banks, but they are also an equal injection because RNW is transferred from banks to firms when the firms default.

If you look back over the whole article, you should notice that, as always when there is no production and no consumption, every time anyone’s RNW increases, someone else’s decreases by exactly the same amount (and vice-versa).

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

Since the firm defaulted, it’s probably insolvent, so its RNW would be increasing from a negative value to something nearer to zero.

‘Y’ for household income, and ‘B’ for banks.

![[Firms] ΔRNW = + D - i. [Banks] ΔRNW = - D + i [Firms] ΔRNW = + D - i. [Banks] ΔRNW = - D + i](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fca37db59-a04e-43ae-91f8-cd7cd3f0e28e_640x128.png)