This is bound to annoy some people. So be it!

I’m not going to discuss theories of what government should be doing. I’m just going to show how it interacts with the rest of the world.

These days, it’s normal for each nation to have a central bank which has a governance role in the monetary system, so it’s best to include the central bank1 in our look at government. Some approaches to economics (notably MMT) treat government and the central bank as a single combined entity. But for now, we’ll treat them as separate. It’s easy to combine them: just put a box around them, and ignore any actions between the government and the central bank.

Another thing I’ll do for clarity is to group households and firms together, giving the group the awkward but appropriate name “non-bank private sector” (NBPS).

There may be some differences between governments of different nations, but I’m not aware of anything major. This article uses the UK government as an example, and is informed by the excellent book An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer, by Andrew Berkeley, Richard Tye and Neil Wilson2. (Free PDF at link).

Here are the ways in which government interacts with the rest of the world. It:

Buys goods and services

Provides public services (e.g. schooling, hospital services, use of public roads)

Makes benefit payments (e.g. pension, unemployment)

Imposes taxes

Collects taxes

Issues “bonds” in exchange for money (borrowing)

Pays bondholders when the bonds mature (repayment)

Pays interest to bondholders

Borrows from the central bank

Repays the central bank

Receives profits from the central bank

In this article, we’ll just look at the first 5 of these interactions, and see how they affect each sector’s raw net worth3. In the next one, we’ll look at the remaining interactions.

Buying goods and services

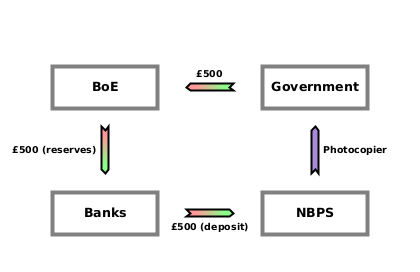

When government buys goods and services (which includes paying government employees for their work), it ensures the seller gets some new money. It usually can’t just transfer money from its Bank of England (“BoE” for short) account to the seller directly, because most sellers don’t have an account with the BoE. So instead, the government instructs the BoE to transfer some of the money in its account to the account of the seller’s bank, and the seller’s bank creates a new “deposit” for the seller (i.e. the bank increases the seller’s account balance).

Essentially the government pays the seller indirectly via the BoE and the seller’s bank.

Here’s an example of the government buying a photocopier from a private sector firm for £500:

As always, look at how each group’s RNW is affected.

The BoE and the Banks are just conduits for a money transfer from the government to the NBPS, so their RNW doesn’t change in any way. (Their RNW both increases and decreases by £500).

The government’s RNW increases by (+ photocopier - £500).

The NBPS’s RNW increases by (+ £500 - photocopier).

Providing public services

The government uses the resources it has available to it to provide public services. These are often provided without the recipients having to pay.

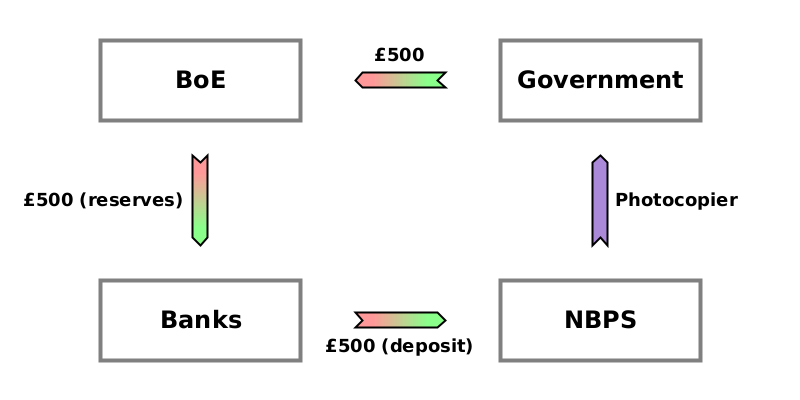

Below is an example of someone receiving medical treatment after breaking their arm.

This is simply provision of a service by government to someone in the private sector.

Services don’t change anyone’s RNW, although the effort and expense of providing the service (e.g. paying doctors) fall on the government sector, while the NBPS hopefully has help in getting a broken arm healed.

Benefit payments

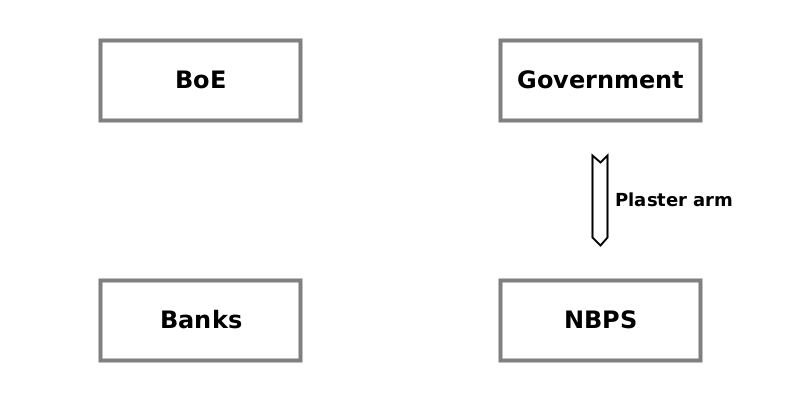

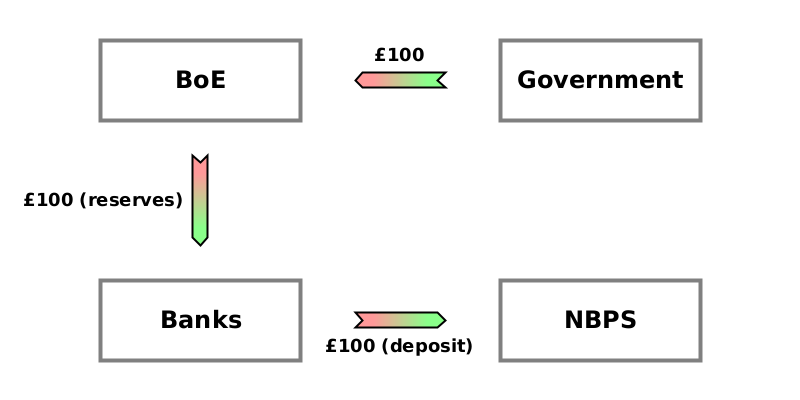

This is a transfer of money to someone in the household sector e.g. a pension payment. Again, it’s an indirect payment via the BoE and the recipient’s bank.

Notice how the payment side is the same as the example above where the government is buying goods and services:

Government’s RNW decreases by £100.

NBPS’s RNW increases by £100.

Tax imposition

One of the powers of the government (and a major reason why it needs to be accountable to the people) is that it can create debts owed by other people. In the case of tax, the debts which the government creates are owed to the government itself.

Instead of arbitrarily imposing a tax on a particular person, the government usually decides a policy on what will be taxed. There are two main types: taxes on what people do, and taxes on what people have or are.

Some common taxes on what people do are sales taxes (or value-added taxes) and income taxes. With a sales tax, if a shop sells something to a customer, it now owes the government a percentage of the money it received. With an income tax, if an employer pays an employee, the employer or employee now owes the government a percentage of the wages.

Property tax is a tax on something people have: a place to live. Simply living there is enough to have the government impose a tax each year so that the person owes the government a certain amount of money, which could depend on an assessment of how much the property would cost to buy. In the UK, Council Tax is used to fund local, rather than national government.

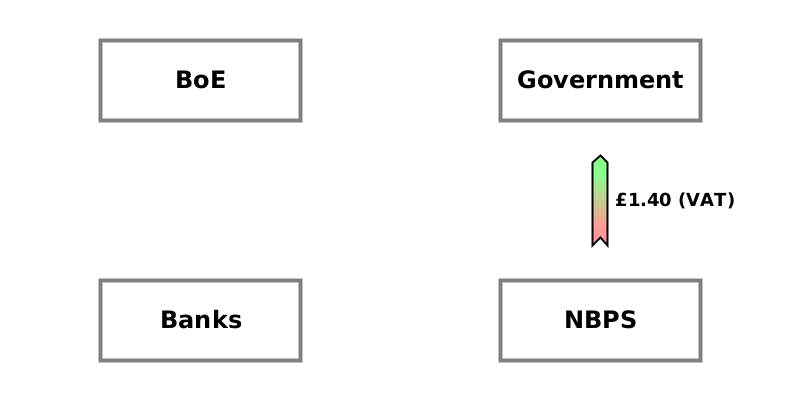

Here is an example of the government imposing a 20% value-added tax on a shop which is selling a £7 product to a customer. The buyer pays £8.40 to the shop, but the shop now owes £1.40 to the government. Since the interaction between customer and shop is internal to the NBPS, all that is shown is the new £1.40 debt.

Government’s RNW increases by £1.40.

NBPS’s RNW decreases by £1.40.

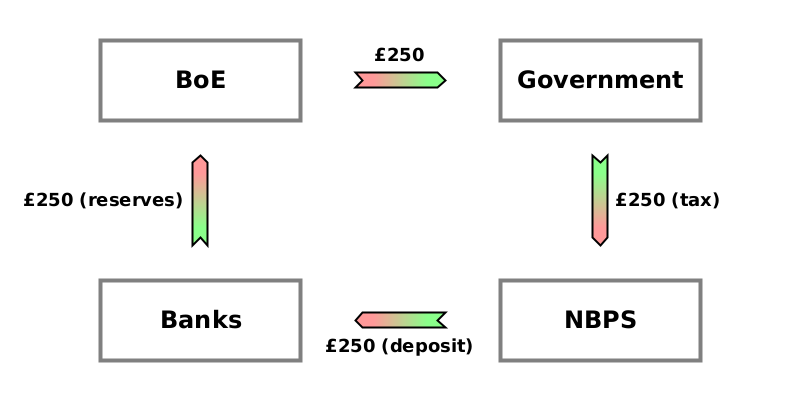

Tax collection

Once tax is owed to the government, the debtor then pays money to the government. This works like the reverse of government paying benefits: the taxpayer pays the government indirectly via their bank and the BoE. In exchange, the government writes off the tax debt.

Here is an example of a taxpayer paying a £250 tax debt.

Notice that, as always when a debt is paid in full, there’s no change to anyone’s RNW. The debt from taxpayer to the government anticipated each person’s final RNW on the assumption that the tax was paid.

Summary

There’s nothing particularly special about the government’s interaction with the rest of the economy, except that it’s able to create debts owed by someone else. Of the interactions we’ve seen here, imposing a tax is the only one in which the government’s RNW increases. Apart from the profits of the central bank, which we’ll see in the next article, this is the government’s only source of income.

As we saw last week, central banks hold bank accounts for other banks and for government.

I actually disagree with how they interpret the accounts which they present, but the analysis is both extremely detailed and very clearly presented. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.