Lots of people talk about double-entry bookkeeping, but I often get the impression that many of them don’t know exactly what it is. So let’s take a look by using an example from earlier, Alice making tables.

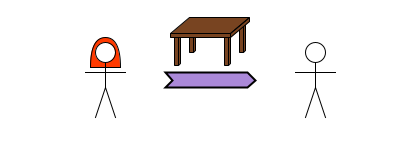

Alice’s business involves repeating 3 steps:

Buying 3 planks for £50.

Using the planks to make a table.

Selling the table for £100.

What is bookkeeping?

Bookkeeping is keeping a record of the changes to a person’s1 assets and liabilities (the changes represented by the arrows in the diagram above), as they occur. The changes for each step in Alice’s table-making are:

Cash ↓ £50; planks ↑ 3.

Planks ↓ 3; tables ↑ 1.

Tables ↓ 1; cash ↑ £100.

This list is actually a form of simple bookkeeping. Even the arrow diagram itself is a form of bookkeeping. (It’s probably less useful for accountants though).

But the most common type is double-entry bookkeeping, which involves T accounts (like we saw in an earlier post).

The principle of double-entry bookkeeping

Most operations of a firm involve a transaction: exchanging one thing for another. (If you look at the arrow diagram for Alice’s table-making, you’ll notice that the arrows are in pairs, with one pointing towards her and one pointing away from her). Double-entry bookkeeping reflects this by recording the thing which is gained and the thing which is lost in different T accounts, each with a cross-reference to the other. The cross-references can help in detecting errors or fraud. And that’s basically it. Here is the double-entry bookkeeping for Alice’s first transaction:

In this transaction, Alice’s raw net worth2 increased by 3 planks, but decreased by £50.

As we saw before, In One Lesson terms:

Increases to RNW are debits, and appear in the left column.

Decreases to RNW are credits, and appear in the right column.

In double-entry bookkeeping, there is always a matching debit for every credit (and vice-versa). That makes obvious sense for an exchange, but what about for a transfer? Suppose Alice simply gives away a table to Bob as a birthday present.

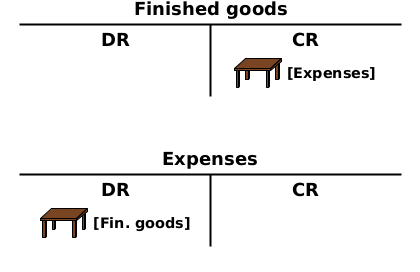

Losing the table is a credit for Alice (conventionally in an account called “Finished goods”). But where’s the matching debit?

Profit and loss accounts

The answer is that there are profit and loss (P+L) accounts which record changes to net worth and/or equity. Increases appear in a “revenue” account, and decreases in an “expenses” account.

So when Alice gives Bob a table, the matching debit is an entry in the expenses account (a decrease in net worth or equity).

(If you’re wondering why a debit in the expenses account is for a decrease in net worth, congratulations—you’re paying close attention! But you’ll have to wait for a future post for the answer).

Similarly, if for some reason Alice’s supplier gives her 3 extra planks for free, that’s a debit, for which the corresponding credit goes in the revenue account (recording an increase in net worth or equity).

Double-entry bookkeeping confusion

It’s easy to get confused by the rules of accounting into believing things about the real world which aren’t true. Here are some examples of mistakes people can make:

Mistake 1. Double-entry bookkeeping means that gaining an asset or losing a liability is always balanced by losing an asset or gaining a liability (and vice-versa).

In reality, there doesn’t have to be this balance. It’s perfectly possible to gain an asset or lose a liability without anything to balance it. The result is just that RNW increases. (Similarly, losing an asset or gaining a liability causes RNW to decrease).

A↑ or L↓ → RNW↑

A↓ or L↑ → RNW↓

There is some truth about it for a limited company, because its equity automatically adjusts so that any changes to its RNW get transferred to its shareholders3. So (at least if the company is solvent) every increase in its assets or decrease in its liabilities is balanced by an increase in its equity liability; and similarly in the opposite direction.

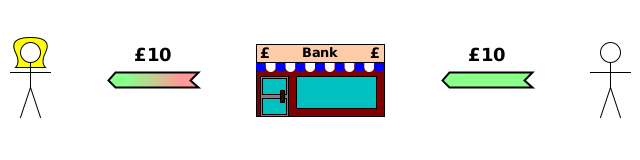

To illustrate this, in the example below, Eve has set up a bank as a limited company. When Bob pays the bank £10 interest, that is a debit to its cash account, and the matching £10 credit (in the revenue account) increases the amount the bank owes Eve.

Mistake 2. Double-entry bookkeeping means that what is gained and what is lost in a transaction have equal value.

This is a result of confusing accounting conventions with reality. When Alice buys 3 planks for £50, it’s standard practice in conventional accounting to assign a £50 “value” to them. But if she was offered a £10 discount, the accounts would show them as having a value of £40, even though they’re exactly the same planks. Accountants aren’t referring to exactly the same thing as economists when they talk about value, and economists shouldn’t feel constrained to follow accounting conventions.

The One Lesson avoids the issue of valuation entirely, simply saying that Alice’s RNW has increased by 3 planks - £50 (or 3 planks - £40, if she gets the discount).

Mistake 3. Double-entry bookkeeping is needed to ensure that assets - liabilities = (raw) net worth.

Double-entry bookkeeping, when done correctly (every credit has a corresponding equal debit, and vice-versa), ensures that the accounts always show:

assets - liabilities = (raw) net worth

It’s far easier to make a mistake when doing bookkeeping in a single list—maybe adding an asset but not making a corresponding change which decreases other assets, increases liabilities or increases RNW.

But that doesn’t mean that we need double-entry bookkeeping to ensure that assets - liabilities = RNW. That’s always true. Unlike assets and liabilities, RNW isn’t a thing in its own right: it’s just something which is calculated from them. Even if we didn’t do any bookkeeping at all, we could always check what assets and liabilities we have4, and then calculate RNW from them by subtracting the liabilities from the assets. If the accounts say that assets - liabilities ≠ RNW, it just means that the accounts have a mistake in them somewhere.

Summary

Double-entry bookkeeping is just a way to record changes to a person’s (usually a limited company’s) assets and liabilities.

Every transaction is recorded in two separate T accounts: a debit in one account and a credit in another. The two entries are cross-referenced to help to detect errors or fraud.

Remember that double-entry bookkeeping is only keeping a record of changes to assets and liabilities. The actual assets and liabilities exist independently of the accounts. Where they disagree, the real world is the one which is correct!

“Person” can refer to a real person or a corporation such as a limited company or government.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe.

Increases in the limited company’s RNW are transferred to shareholders by creating a new equity debt, and decreases in its RNW are transferred by writing off some of the existing equity debt.

This generally takes a long time, which is why it’s a a good idea to keep accounts.

![[T - Cash] (CR) £50 {Raw mat.}. [T - Raw materials] (DR) plank×3 {Cash} [T - Cash] (CR) £50 {Raw mat.}. [T - Raw materials] (DR) plank×3 {Cash}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F774e9d10-e78d-432a-99fc-16f0bde24469_1280x200.png)

![[T - Finished goods] (CR) table {Expenses}. [T - Expenses] (DR) table {Fin. goods} [T - Finished goods] (CR) table {Expenses}. [T - Expenses] (DR) table {Fin. goods}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb40ce409-5680-4c93-960d-d2e1008aa999_1280x200.png)