In my first post on double entry bookkeeping, I mentioned that even when a person1 is involved in a transfer rather than an exchange, there is still both a debit and a credit in their accounts. The first entry is the action itself, and the second entry is in the profit and loss accounts (revenue or expenses). But what do these P&L accounts actually tell us about the real world? The answer is more subtle than many economists realise.

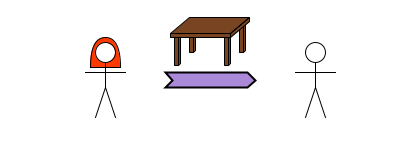

Here’s the example from that post, where Alice gives Bob a table:

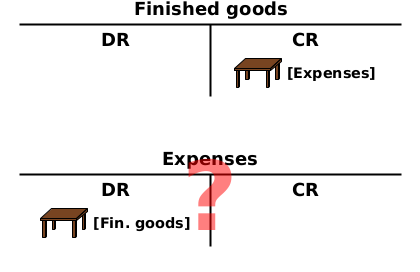

And the accounts look like this:

I’ve written that debits are increases to raw net worth2, and credits are decreases to RNW. The credit in the “Finished goods” account—corresponding to the tail of the purple arrow—shows that Alice’s RNW has decreased by the table. But there’s also a debit in the “Expenses” account. Is there an arrow missing from the diagram which cancels out the decrease to RNW?

The answer is: it depends. Are these accounts for Alice as an individual, or for a limited company which she’s operating?

If it were actually a limited company giving the table to Bob, this debit in the “Expenses” account represents a decrease in equity (which is the residual debt owed by the company to the shareholders after all other liabilities have been paid). Decreasing equity is a write-off of debt: one of the 7 economic actions. So in fact the debit in the “Expenses” account does represent an action (the green-to-pink arrow below) which cancels out the credit from giving the table to Bob.

What would have been a decrease in the company’s RNW is compensated for by the shareholders (in this case, Alice) losing an equal amount of equity, leaving the company’s RNW where it had been before3.

But for an individual (as in the original diagram), they have no equity, and giving away the table simply decreases their RNW with no compensating action. This decrease is already recorded in the credit to their “Finished goods” account, and the debit shown in their “Expenses” account is really just a fictional entry, which only exists to “balance the books”.

This isn’t a criticism of accountants or accountancy—one of the principles of double entry bookkeeping is recording all changes in two separate places so that errors or fraud can be detected more easily. And there is something to be said for finding a way to avoid the need for exceptions to the rule that every debit has a matching credit and vice-versa. But economists need to understand the fundamental difference between equity and net worth. Equity is an actual liability which is owed to the shareholders. By contrast, RNW isn’t really a liability: it’s just treated like one to make the accounting consistent.

Summary

In double-entry bookkeeping, when there appears to be only a single debit or credit, a corresponding credit or debit appears in the P&L accounts (revenue/expenses).

For a limited company (or similar), this matching credit/debit is an actual economic action, which changes what is owed to the shareholders, and leaves its RNW unchanged.

For an individual, the matching economic action doesn’t really exist. Their RNW actually changes.

Unless economists understand this difference, any conclusions they draw will end up being about an imaginary world in which there’s no way of creating or destroying wealth. This is particularly dangerous if they give advice to policy makers about what to do in the real world based on the imaginary world.

“Person” can refer to any entity with its own balance sheet, so either a real person or a corporation (limited company, government, charity, trust, etc.)

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe.

A solvent company’s RNW is always zero, because the equity liability is always the assets minus the other liabilities.

![[T - Finished goods] (CR) table {Expenses}. [T - Expenses] (DR) table {Fin. goods} [T - Finished goods] (CR) table {Expenses}. [T - Expenses] (DR) table {Fin. goods}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F965c636a-b820-49c0-b9f3-4893f503526c_1280x200.png)