It’s important to remember that conventional accountancy is a model of the real world. That just means that some aspects of the real world are included in it, and others aren’t. Like all models, it exists to help us to answer certain questions. But we have to be cautious when we interpret it, especially when we’re trying to answer questions which it wasn’t designed for. In this post we’ll look at how accountancy does what it’s designed for, how it can be misunderstood by economists, and how the One Lesson can help to make sense of it.

One of the main purposes of accountancy is to assess a “fair value” for a firm, so managers and investors can quickly see how well a firm is doing compared to the same firm at a different time, or compared to a different firm. To do this involves reducing each asset and liability to a quantity of money, making some assumptions about value, and guessing what might happen in the future. The way that accountancy treats profits can be particularly confusing for economists, who can easily draw wrong conclusions.

Giving everything a money value

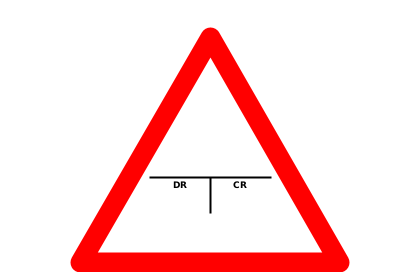

Accountants assign a money “value” to every asset and every liability. (This is the idea of money being a “unit of account”).

Deciding what “value” to use comes from a combination of conventions and judgement. Two common ways to decide what “value” to assign to an asset are:

How much money it cost originally1

How much money you expect it could be sold for today (based on how much money similar things have been sold for recently)

These could be very different.

Economists shouldn’t assume that the money value assigned to an asset in the accounts is what it could be sold for, or that it is what the asset is “worth” in some objective sense. And similarly, the money value of a liability in the accounts may not be what it will cost to pay what is owed2.

The One Lesson uses raw net worth3 to avoid any subjectivity, as well as to distinguish between different types of thing which happen to be considered “worth” the same quantity of money (including that quantity of money itself). For example, someone can only eat if they have food: it’s not enough to have enough money to buy food. (They can swap the money for food, but this reduces the amount of food available for the seller to eat).

Assuming equal values

By convention, accountants assume that when someone buys something, its money value, at least to start with, is however much money they spent on it. (It can be adjusted later if it’s something which deteriorates with time or use).

When Alice spends £50 on 3 planks, her accountant would write a £50 credit in the “Cash” account and a £50 debit in the “Raw materials” account, as we saw above, so in the conventional accounting model, there is no change to Alice’s net worth.

Economists should be aware that something important has changed. Alice has less money, but more raw materials which she needs for her production. This couldn’t have happened if nobody was selling planks. Simply having money is not enough for manufacturing to take place4.

As far as the One Lesson is concerned, Alice’s RNW (and, if Alice is operating a limited company, the firm’s “raw equity”) does change: it has increased by (3 planks - £50).

Anticipating the future

To assign a “fair value” to a firm, accountants have to consider what’s likely to happen in future. There are many examples. Here are a few.

Provision for bad debts. Firms may find that a certain proportion of debts owed to them are defaulted: the debtor fails to pay. An accountant might add a “provision for bad debts” liability to the accounts to anticipate the decrease in the firm’s equity when defaults actually occur. Here’s an example where Bank of Eve has added a provision, expecting that £1M of the £8M loans will default.

Notice that the existence of the provision entry reduces equity from £4M to £3M, giving the shareholder(s) a more realistic impression of what their shares are worth.

When the actual level of defaults is eventually known, an entry can be added to the accounts just showing the difference between what was expected and what actually happened5.

Economists shouldn’t assume that this balance sheet entry representing an expected future loss means that one firm can gain a new liability without someone else either gaining a new asset (write off debt) or losing an existing liability (transfer liability). To assess the firm’s fair value, conventional accounts include an anticipated future action, even though it’s unknown yet which (if any) of the firm’s debtors will actually default.

Since most economic models try to predict people’s behaviour, based on the state of the economy, they must do one of the following:

Assume defaults won’t happen;

Pretend that the firm can gain a liability without anyone else gaining an asset or losing a liability; or

Find some way to represent that a default is anticipated, but it’s not yet clear which debtor will default.

The One Lesson’s approach avoids these difficulties by saying that the default doesn’t occur until the debtor actually fails to pay, so that both sides of the action6 are recognised at the same time. This works because the One Lesson model doesn’t try to predict people will do, based on the state of the economy. It only says what the state of the economy will be, based on what people do.

Goodwill7. This “asset” is opposite to provisions, anticipating the increase in the firm’s equity from future profits. It can be added to the accounts when one firm buys another for more money than its reported equity. This avoids it showing up as a loss in the accounts of the purchasing firm.

Economists should realise that paying more for a firm than its current equity doesn’t really increase its assets. Goodwill is just an expectation about future profits, and the purchase is just a speculative decision, anticipating the equity increasing later because of these profits.

Again, the One Lesson avoids the issue entirely by recognising profits only when they occur, not before.

Intellectual property. If a firm registers a patent, preventing others from making use of its invention, its accounts could show this as an asset. But again, it doesn’t own, and isn’t owed, anything extra at this point. This “asset” anticipates the additional profits which the firm can make, either by being able to charge more for its products (because competitors aren’t allowed to use the invention, meaning that it may cost them more to produce similar products), or from suing anyone who does use it.

Economists should realise that patents, and other intellectual property, don’t add to the world’s wealth, but just affect how wealth is distributed in the future.

The One Lesson only recognises the effects of the patent existing. If a patent enables a firm to sell a product for £200 instead of £100, the only difference is in the fact that the buyer transfers an extra £100 at the time of the sale. As always in the One Lesson, since nothing is being produced or consumed, registering a patent doesn’t add to anyone’s RNW without taking an equal amount from someone else’s.

I mentioned in an earlier article that intellectual property (like patents and copyrights) can be thought of as a contingent debt: it can become an actual debt if some event occurs, in this case someone copying the invention.

Profits

Whenever Alice’s firm manufactures a table, her accountant credits the “raw materials” account (because the planks have been used up) and debits the “finished goods” account (because the firm has a new table ready to sell).

As always, suppose the planks cost £50 and tables normally sell for £100. You might believe that the firm has made a £50 profit at this point, but that’s assuming that the firm actually manages to sell the table. Because of this risk, accountants are conservative when it comes to recognising profits (i.e. showing that they’ve happened). They don’t do it until the finished product has actually been sold8.

![[T - Raw materials] (CR) Plank ×3 {Raw mat.}: £50. [T - Finished goods] (DR) Table {Raw mat.}: £50. [T - Raw materials] (CR) Plank ×3 {Raw mat.}: £50. [T - Finished goods] (DR) Table {Raw mat.}: £50.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4a59f0d4-5a01-485f-9d9a-3a26b7859674_1280x200.png)

Economists need to be very careful about interpreting this. Within the accounts showing the sale, it appears that simply selling the table makes it more valuable (the firm loses a £50 asset, and the buyer gains a £100 asset), and created a profit for the manufacturer. But this isn’t right.

The One Lesson shows clearly what is actually happening. At each stage, even when conventional accounts show one thing being exchanged for another thing of the same “value”, there is an actual change to which assets the firm has. Profit is just how much the firm’s equity has changed. So, at each stage, we can look at the firm’s profit since the point in time before it bought the raw materials:

Buying planks for £50. Firm’s profit = + 3 planks - £50

Manufacturing table. Firm’s profit = + table - £50

Selling table for £100. Firm’s profit = + £50

If the table was never sold, and ended up rotting in a warehouse, the final step would have been:

(b) Table rots. Profit = - £50

In other words, the firm would have made a loss of £50.

Both buying planks and selling the table are transactions involving zero-sum actions: the combined RNW of the people involved doesn’t change, and neither does the whole world’s RNW. The only place where the world’s RNW does change is the production (and the consumption of raw materials). This is where the profit is created. Having already made a profit (of uncertain value) by transforming one asset into another, the firm is able to sell the table for more money than it cost to buy the planks.

It’s hard to overemphasise how useful RNW is for understanding the idea of profit. It has been a controversial idea for centuries, and even today, economists get confused about “where the extra money comes from”, and whether the firm ending up with more money means someone else is worse off.

Summary

Conventional accountancy exists to help to assign a “fair value” to a firm, and it does this job well. It isn’t designed to help to explain economics, and economists need to be conscious of this when they use accounts as an economic model, or they are in danger of drawing seriously incorrect conclusions.

By using different conventions from conventional accountancy (in particular, by not allocating money values to assets and liabilities, and not attempting to predict the future), the One Lesson’s RNW model uses the concepts of accounting (assets, liabilities, equity, net worth), but makes them far more relevant to the study of economics. It shows clearly that profit isn’t a result of selling a product, but of producing something more valuable than was consumed in the process.

For an asset which wears out over time, this value is adjusted downwards over its expected lifetime by crediting the asset and debiting equity/net worth. This adjustment is called depreciation.

Even if what is owed is a quantity of money, there could be a transaction cost for making the payment.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a heterogeneous sum/difference, meaning that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

Unless you’re making something out of banknotes or coins, I suppose.

This would credit loans and debit expenses.

Creditor loses asset; debtor loses liability.

I learned about this in 2010 from Jonathan Weil, writing at the time for Bloomberg News.

This involves: debiting cash £100 and crediting income £100; and crediting the “Finished goods” account £50 (for the table) while debiting a “Cost of sales” account (a decrease in equity) by £50. This YouTube video does a nice job of explaining a similar situation: a window-cleaning service where the “raw materials” are cleaning products.

![[T - Cash] (CR) £50 {Raw mat.}: £50. [T - Raw materials] (DR) plank ×3 {Fin. goods}: £50. [T - Cash] (CR) £50 {Raw mat.}: £50. [T - Raw materials] (DR) plank ×3 {Fin. goods}: £50.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F22288bb2-09d5-45ee-b522-79c104cba2e1_1280x200.png)

![(BS - Bank of Eve) [A] Cash (£2M), Loans (£8M), Total (£10M); [L] Deposits (£6M), Provision (£1M), Equity (£3M), Total (£10M) (BS - Bank of Eve) [A] Cash (£2M), Loans (£8M), Total (£10M); [L] Deposits (£6M), Provision (£1M), Equity (£3M), Total (£10M)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb24bb55c-71b1-4daf-8cf5-7d16276e1806_640x300.png)