Robinson Crusoe managed to provide for all his own needs. (He didn’t have much choice). If you like obscure words, he was the ultimate example of autarky.

But there’s only so far most people can go in producing everything they consume. Adam Smith, in his surprisingly readable The Wealth of Nations1, explained that people and nations become far wealthier if the people become specialists, producing vastly more than they need of just one product (or perhaps a few), and then trading their surplus products for other people’s surplus products of different types. For example, a baker can produce enough bread for many people, and trade most of the bread for meat, beer, or furniture.

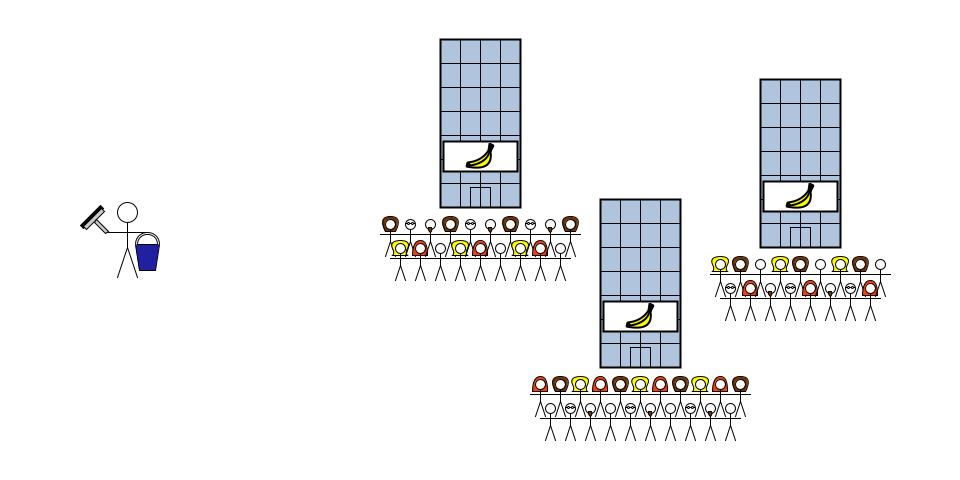

So in a developed economy, most production isn’t done for producers to consume themselves, but for selling to someone else. We can think of a firm as a person (or organisation) who sells goods or services, which they’ve either produced themselves or bought from someone else (such as a shop). It can be as small as a self-employed window cleaner, or as big as a multi-national corporation with hundreds of thousands of employees around the world.

Let’s look at an example of a firm in action.

Making tables

Alice likes working with wood, and decides to earn a living by producing tables. For now, let’s assume she has all the tools she needs2.

So Alice is ready to get to work. She repeats the following sequence:

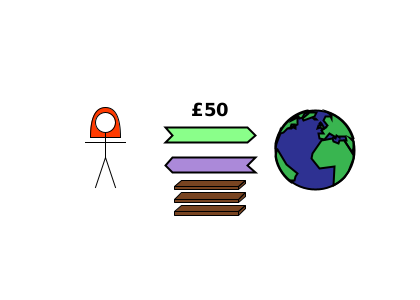

Buy 3 wooden planks for £50 cash.

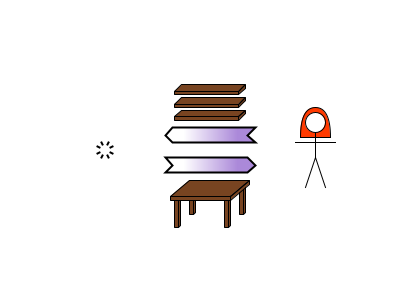

Use her effort, skill and tools, to convert the wooden planks into a table.

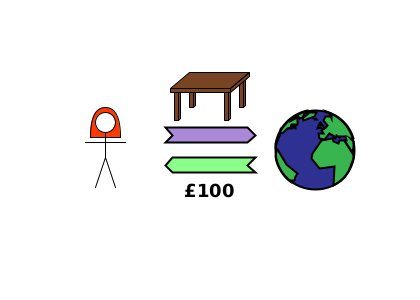

Sell the table for £100 cash.

Here are diagrams showing the changes to everyone’s raw net worth3 for each step. (The earth picture represents the whole world except for Alice).

Buy raw materials

This is just swapping an existing debt asset (the cash) for an existing tangible asset (the planks).

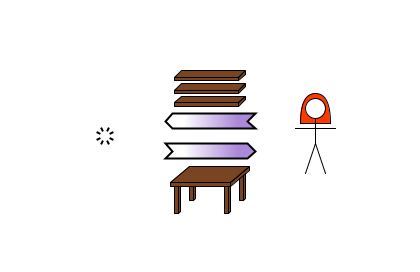

Produce

In the process of producing a table, Alice uses up (consumes) the planks. The same wood is still there, but it’s now in the form of a table instead of planks: she doesn’t have both.

Sell product

As with buying the planks, this is just swapping an existing debt asset (the cash) for an existing tangible asset (the table).

Each time Alice goes through this 3-part sequence, she ends up with the same liabilities as she started with, but £50 more cash. Her RNW has increased by £50, and we can call this her profit. She can then spend that money on other things she’d like—shelter, food, heating, cinema tickets, etc.

That’s the whole idea. She produces what she’s particularly good at, and uses the surplus to buy things which other people can produce better than her.

Profit

Some people are wary of, or even hostile to, profit. In 2013, Russell Brand said the following in an interview with Jeremy Paxman on BBC Newsnight:

David Cameron [then UK prime minister] says “Profit isn’t a dirty word.” I say profit is a filthy word, because wherever there is profit there is also deficit.

Was he right? Alice has made a £50 profit. Does that mean the rest of the world is £50 worse off? Let’s investigate by looking at a single diagram showing all 3 stages of Alice’s table production:

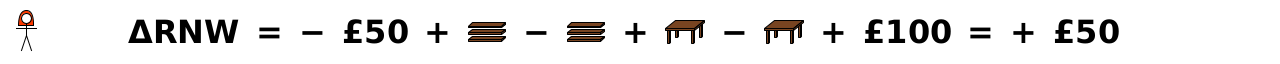

First, let’s double-check what happens to Alice’s RNW. Remember that arrows pointing towards her increase her RNW, and the arrows pointing away from her decrease her RNW. So her change in RNW is given by:

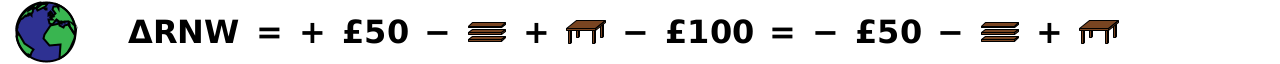

Check carefully that this corresponds to the previous diagram. Then check the simplification: the planks and table are both added and subtracted, cancelling each other out. Also the £50 she lost (buying the planks) offsets the £100 she gained (selling the table), so it leaves her with just a £50 profit. But has the rest of the world made a £50 loss?

The only simplification here is that gaining £50 and losing £100 is the same as losing £50. So the rest of the world has £50 less cash, but if you look after the final ‘=’, you’ll see that’s not the whole story. It also has 3 fewer planks, but on the positive side, it now has a table which it didn’t have before. In effect, the rest of the world was happy to pay Alice £50 to convert 3 planks into something more useful: a table.

This scenario wasn’t a zero-sum game, as Russell Brand suggested 10 years ago, because there was production. Alice didn’t get her profit by taking it from someone else: she created it by converting something which other people considered less valuable into something more valuable to them.

Some people might be wondering why the rest of the world didn’t just turn the planks into a table themselves, and save themselves £50. They could have, but there are plenty of good reasons to pay Alice to do this instead:

They might be less skilled in woodwork

They might not have the necessary tools

They might not have the time

They’re probably better off producing something which they specialise in instead, and using some of their profit from that to buy a table from Alice

So Russell Brand made a mistake here. We all make mistakes, but it’s important to learn from them because getting something like this wrong can lead you to make some very bad decisions. Assuming that profit (producing more than you consume in the process) is bad could lead to some truly awful government policies.

I hope you find this a good illustration of how useful the One Lesson is at seeing through errors in economics.

If you’ve never looked at this, please do read the first 2 chapters. It’s only 5½ pages, and it really brings to life the interconnection of the economy. https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/smith1776_1.pdf

We’ll look at capital equipment in a follow-up post. Capital equipment just means things which make it easier to produce other things.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe.

![[1] (transfer DA) Alice->world {£50}; (transfer TA): world->Alice {planks}. [2] (consume) Alice->void {planks}; (produce) void->Alice {table}. [3] (transfer TA) Alice->world {table}; (transfer DA) world->Alice {£100}. [1] (transfer DA) Alice->world {£50}; (transfer TA): world->Alice {planks}. [2] (consume) Alice->void {planks}; (produce) void->Alice {table}. [3] (transfer TA) Alice->world {table}; (transfer DA) world->Alice {£100}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F55be342a-787c-40aa-887f-bc6a322dd933_630x300.png)