In the first post about firms, we saw how Alice manufactured tables from planks, and was able to make a £50 profit by buying planks for £50 and selling the resulting table for £100. Even though she made a £50 profit, it didn’t mean that the rest of the world made a £50 loss, because despite having £50 less money, it now had a table instead of some planks.

Manufacturing adds to the world’s raw net worth1. So do other ways of producing tangible assets: harvesting and mining. We can reasonably say that Alice created the profit herself. The rest of the world was happy to sell her the planks for £50, and to buy a table from her for £100.

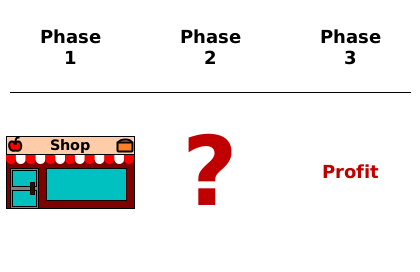

But what about a shop which simply buys products at one price from a producer (or wholesaler) and then sells the same products to consumers at a higher price? When the shop makes a profit, does this mean that the rest of the world has made a loss, and if so, is the shop cheating them?

Bob’s shop

Let’s look at an example. Bob has a shop, and buys apples from Frank, a farmer, to sell to the rest of the community. Every week, he pays £10 for 100 apples (10p each on average), and sells them for 20p each.

We can read the changes to Bob’s RNW from the diagram above:

So Bob’s made a £10 profit. What about the rest of the world? (Here, the earth picture represents the whole world except Bob).

So in this case, the rest of the world has in fact made a £10 loss. Is Bob scamming them?

Not so fast! Bob isn’t stopping Alice, Charlotte, Dom and Eve from going to Frank’s farm and offering to buy apples from him directly2. Sometimes farms do have their own shop. They could agree a price of 15p per apple, so both Frank and the customer each save 5p per apple compared to dealing with Bob. But there are some good reasons why this often isn’t the best arrangement, either for the consumers or the farmers.

First for consumers. If Alice buys apples once a week, and eats one a day, then for every 7 apples she buys she also has to travel to Frank’s farm, which has a cost (for fuel or fares). If it costs her £5, then even though she saves 35p for a week’s apples compared to buying them from Bob’s shop, she’s actually worse off by £4.65 each week. Obviously that’s not worth it.

And it’s the same for all of the other things she wants to buy. Travelling to every single producer to buy a small number of goods is really inefficient. Instead, she can save on travel by going to Bob’s shop where she can buy all the things she wants in one place.

Now think about Frank. He could set up a farm shop, and sell to people directly, and get £15 per week for his 100 apples instead of £10. But he doesn’t have time to stand behind a till all day, waiting for the occasional customer to buy an apple. And if he employs Charlotte to work at the shop, and has to pay her £10/hour, it’s only worth it if the shop is open for less than 30 minutes per week. That’s not going to provide a very good service for customers.

And service is the key to this. The reason that Bob is able to make a profit running his shop is that he is being paid for the service he provides. For Frank, he takes over the responsibility of selling to lots of individual consumers. All Frank has to do is meet Bob once a week, and in the space of a couple of minutes can swap 100 apples for £10. The rest of his week is then free for him to do his other work. And for consumers, Bob is providing a place where they can browse and buy a variety of products in a single place, saving them the cost and time of travel.

Here’s a fuller diagram of Bob’s apple trading, showing these services which he provides. Bob makes a living by being an intermediary (a “middle man”) between producers and consumers. If the profit he makes is less than what producers and consumers save by using his service, producers, consumers and Bob himself are all better off than they would be otherwise.

It’s important to remember that goods and services don’t magically get from producers to consumers: there are costs involved. If someone can find a way to make the process more efficient (e.g. in wholesale, retail or transport), they can earn a living by providing a service from which everyone benefits.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe.

It is possible for a producer to sign an exclusive contract with a retailer, in exchange for the retailer paying a higher price. If there is plenty of competition, this needn’t be a problem, but if not, the retailers could charge far more to consumers because they have nowhere else to buy the products. Consumers need to be wary of this happening.