In the last article, we looked at the financial economy: creating debts, transferring debt assets and liabilities, and writing off debt (the actions with pink and/or green arrows). Without them, all we’d have is a barter economy, or a system of informal reciprocation. Here we’ll see how to understand the whole financial economy: every action involving debts which has ever occurred.

We’ve seen that the whole real economy can be understood as a huge number of chains, one for each tangible asset (or service) ever produced.

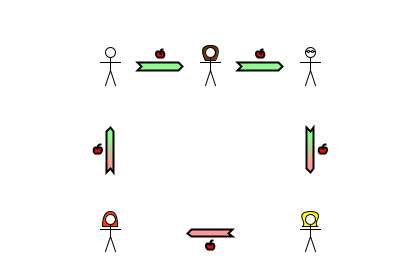

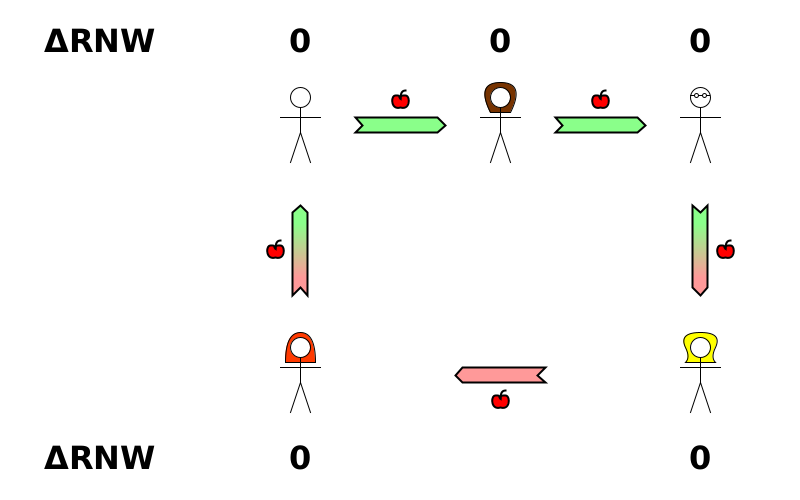

Here we’ll see that the whole financial economy can be understood as a huge number of loops, one for each debt ever created. (TL;DR: below is a typical debt loop. If you’re very familiar with the One Lesson, this may be enough. Otherwise keep reading).

Life cycle of a debt

Every debt, past, present or future, goes through essentially the same life cycle: first it’s created, then the debt asset may be passed from one creditor to another, while in parallel the liability may be passed from one debtor to another, and eventually the final creditor agrees that the final debtor no longer owes the debt. Let’s look at an example—a debt for one apple:

On Monday, Alice promises to give Bob an apple on Friday. (Alice owes an apple to Bob).

On Tuesday, Bob transfers the debt asset to Charlotte. (Now Alice owes an apple to Charlotte).

One Wednesday, Eve agrees to become the debtor, relieving Alice of that responsibility. (Now Eve owes an apple to Charlotte).

On Thursday, Charlotte transfers the debt asset to Dom. (Now Eve owes an apple to Dom).

On Friday, Dom agrees that Eve no longer owes the apple.

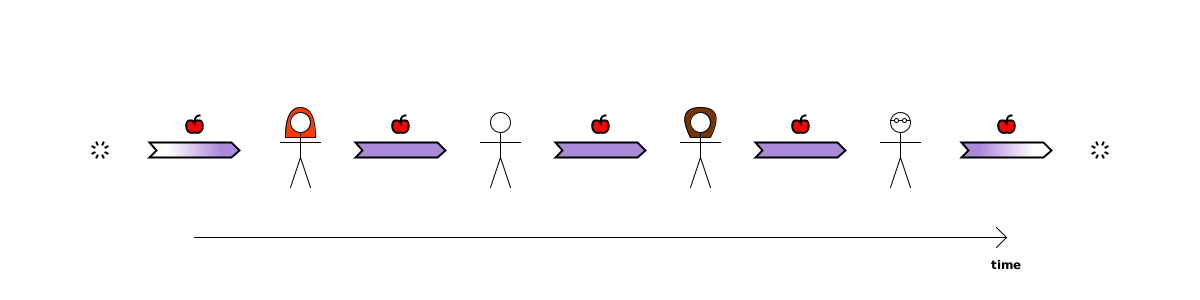

We won’t consider any actions in which something is given in return. Those actions relate to different goods, services or debts, and each belongs to its own group of actions. Here, we’ll just see what effect the actions relating to this debt have on each person’s raw net worth1 at each stage from debt creation to debt write-off, compared to what would have happened if the debt had never been created.

(In the diagrams, the changes to Bob’s, Charlotte’s and Dom’s RNW are shown above them, and the changes to Alice’s and Eve’s are shown below them).

First, before the debt was created:

Obviously nobody’s RNW has been changed by these zero actions.

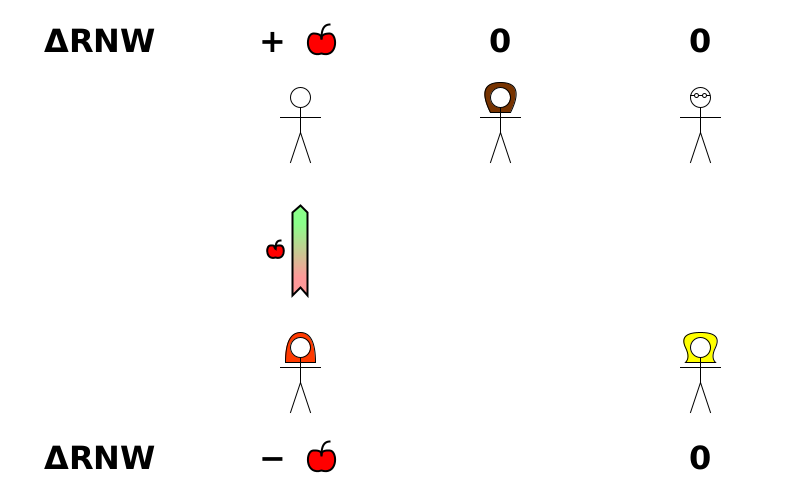

Now consider what happens when Alice creates the debt to Bob:

At this point, Bob’s RNW has increased by an apple, and Alice’s RNW has decreased by an apple. Nobody else’s RNW is affected.

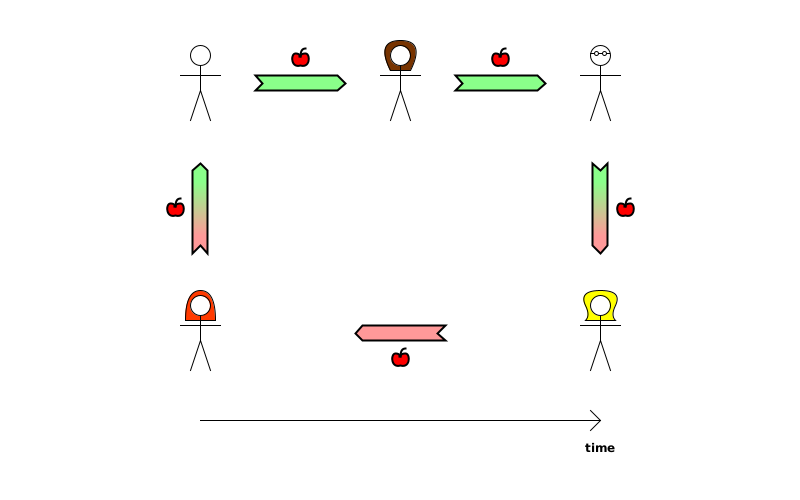

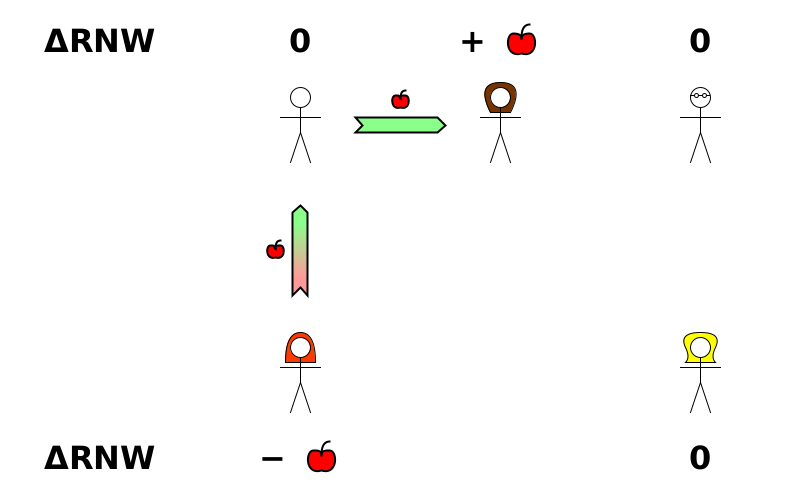

What about after Bob transfers the debt asset to Charlotte?

Now Bob’s RNW is back where he started (he has an arrow pointing to him and another pointing away from him), but Charlotte’s has increased by an apple. Alice’s RNW is still reduced by one apple.

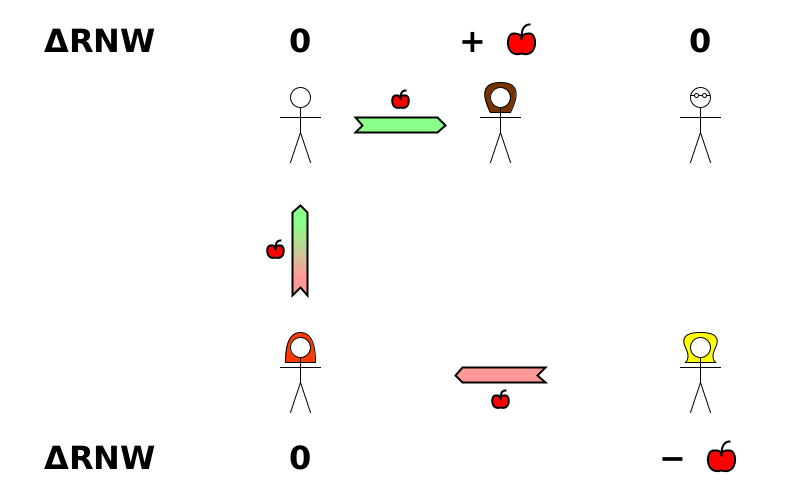

What happens after Eve takes over the debt from Alice?

When the liability is transferred from Alice to Eve, it increases Alice’s RNW, and decreases Eve’s. It’s a transfer of RNW in the opposite direction: from Eve to Alice2. Now Alice’s RNW is restored to her starting point, but Eve’s has decreased by an apple.

This is a good point to follow the arrows carefully. There is currently a chain of them:

Eve→Alice→Bob→Charlotte

You can think of this as Eve having transferred one apple from her RNW to Charlotte, but indirectly—via Alice and Bob3. Notice how this is entirely consistent with Eve’s RNW decreasing by one apple and Charlotte’s RNW increasing by one apple.

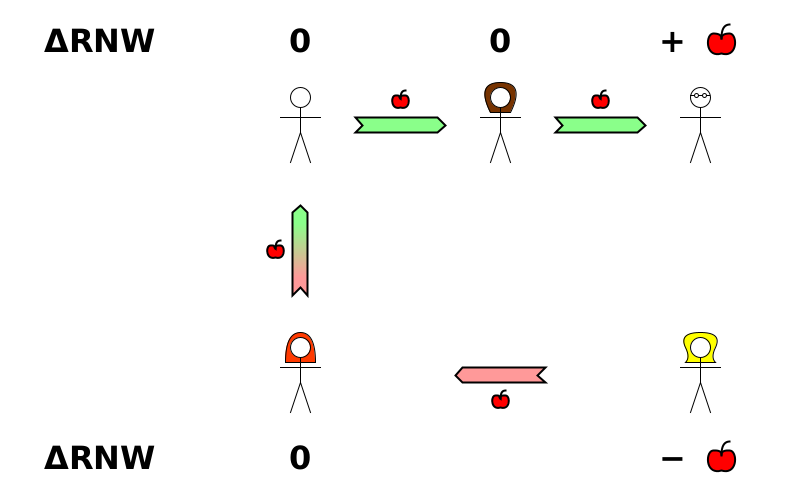

Next, Charlotte transfers the debt asset to Dom:

Now Charlotte’s RNW is back where she started, but Dom’s has increased by an apple. Eve’s RNW is still reduced by one apple. Notice again how there’s a chain transferring RNW indirectly from Eve to, now, Dom.

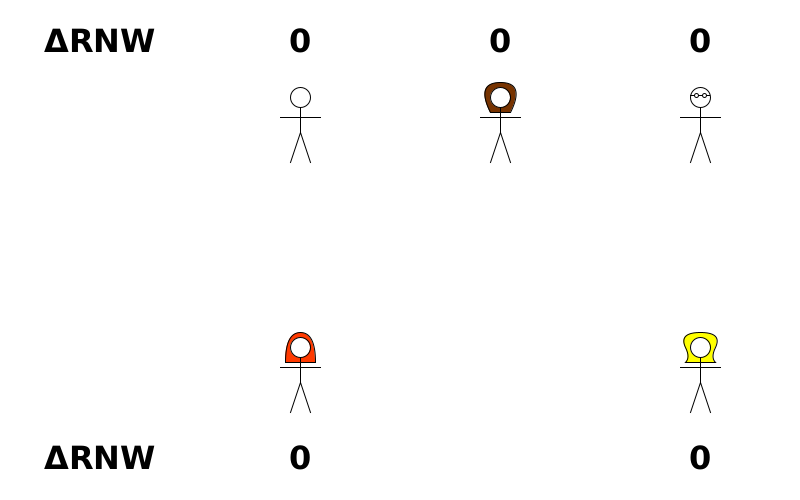

And finally, Dom agrees that Eve no longer owes the debt:

Once the debt has been written off, it completes a loop, and everyone’s RNW is back to its starting point (all the ΔRNWs are 0). The RNW of each of the creditors (the top row of people) first increased by the apple when they gained the debt asset, and then decreased back to the starting point when they gave it up. The RNW of each of the debtors (the bottom row of people) first decreased by the apple when they gained the liability, and then increased back to the starting point when their liability was removed.

The whole financial economy

The whole financial economy is just a vast network of these loops. The effect of a loop of actions is to increase the current creditor’s RNW by the amount of the debt, and to decrease the current debtor’s RNW by exactly the same amount. This effect lasts for the duration of the debt. (Before the debt was created, and after it is written off, nobody’s RNW is affected by it).

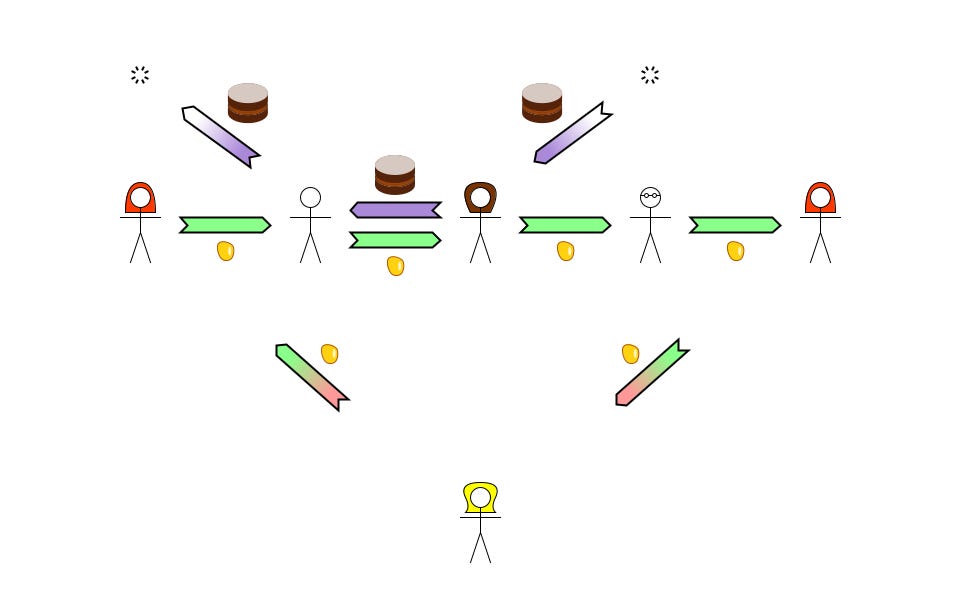

These loops can interact with tangible asset chains, or with other debt loops to form transactions. Let’s look at part of the bank lending example4. It actually consists of 4 chains and 2 loops:

A chain for the amber.

A chain for the book.

A chain for the cake.

A chain for the DVD.

A loop for the debt (for a piece of amber) first owed by Eve to Alice.

A loop for the debt (for a piece of amber) first owed by Alice to Eve.

Here we’ll just look at numbers 3 and 5.

First look at the chain for the cake:

void → Charlotte → Bob → void

Charlotte produced the cake, and transferred it to Bob, who ate it.

Then look at the loop for the debt of a piece of amber:

Eve → Alice → Bob → Charlotte → Dom → Alice (again) → Eve

Eve created a debt to Alice5, the debt asset was passed from Alice to Bob to Charlotte to Dom and back to Alice6, and finally Alice agreed that Eve no longer owed the debt7. (The liability was never transferred: it stayed with Eve for the duration of the debt).

Apart from consuming the cake, each of the action arrows is part of a transaction8, most of which aren’t shown because the diagram would become too cluttered. The one transaction which is shown is between Bob and Charlotte, where Bob swapped Eve’s IOU (for one piece of amber) for Charlotte’s cake.

Hopefully you can see from the one transaction which is shown how transactions are simply places where different chains and loops interact.

Summary

To understand the financial economy, we can break it into smaller pieces: one group of actions for each debt ever created. Each of these forms a loop in which each participant’s RNW both increases and decreases by the amount of the debt. A creditor’s RNW first increases and then decreases, undoing the increase, while a debtor’s RNW first decreases and then increases, undoing the decrease.

For the duration of the debt’s existence, its effects on everyone’s RNW are:

The current creditor’s RNW increases by the amount of the debt.

The current debtor’s RNW decreases by the amount of the debt.

Nobody else’s RNW is affected by the debt.

Where a loop interacts with another loop or a chain, it is a transaction where one person is swapping some of their RNW for some of the other person’s.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

There’s an analogy with electrical current in a wire. We say that current is flowing in one direction because negatively-charged electrons are flowing in the opposite direction. An even better analogy is the movement of a “hole” in a semiconductor.

It’s vaguely interesting to note that the chain of transfers of RNW from Eve to Charlotte is at first backwards through time (Eve → Alice → Bob) before going forwards again (Bob → Charlotte). Obviously nothing real is going backwards through time: the liability is just being passed between debtors forwards through time, which is equivalent.

See the article on The Real Economy: the left side of the first arrow diagram.

In exchange for Alice creating a new debt to Eve, not shown here.

Each time in exchange for a tangible asset, not shown here.

In exchange for Eve agreeing that Alice no longer owed her debt, not shown here.

Producing the cake is part of a transaction in which Charlotte consumes the ingredients (butter, sugar, eggs, flour), each belonging to its own chain.