You might have thought that money and banking (which have been around for a long time) were fully understood by economists, and completely uncontroversial by now.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Fortunately the One Lesson of economics shows us how to make sense of both, and equips us to spot flaws in the many arguments about them. In this post, we’ll see how different approaches to money (and banking) can solve an important problem: how can people trade what they have (or will have in future) for what they would prefer to have, without having to do an impossible amount of coordination between people.

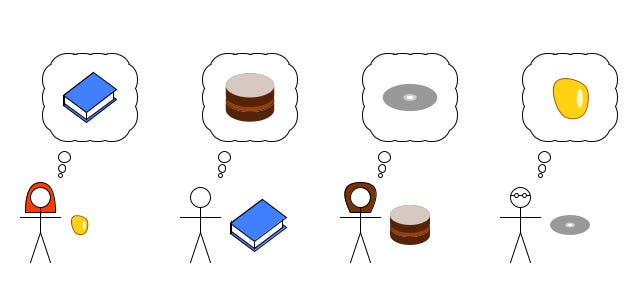

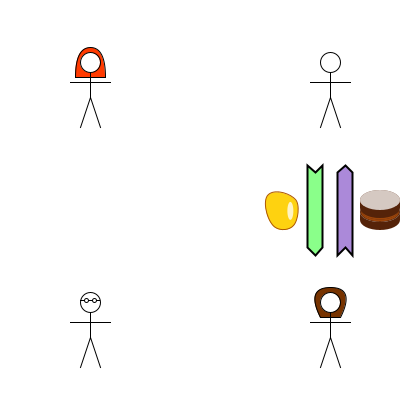

The scenario

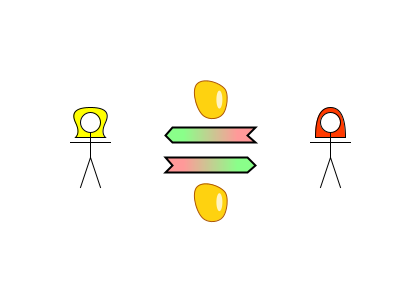

Here’s the problem to be solved:

Alice has some amber, but wants a book.

Bob has a book, but wants a cake.

Charlotte has a cake but wants a DVD.

Dom has a DVD, but wants some amber.

To keep the example as simple as possible, we’ll assume that everyone considers it a fair trade to exchange what they have for what they want.

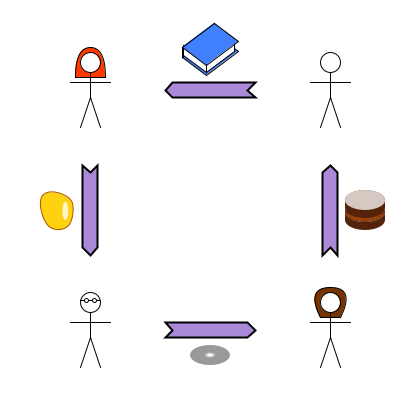

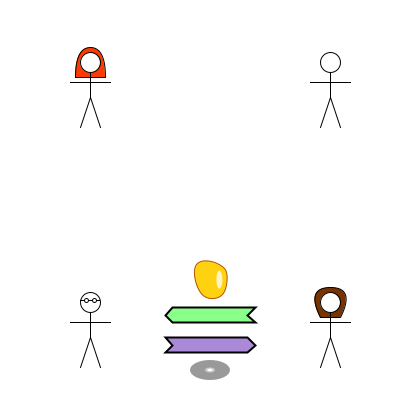

One big trade

One simple way to solve the problem is for Alice, Bob, Charlotte and Dom to meet up, stand in a circle, and pass what they have to the person to their right (and receive what they want from the person on their left).

Advantages

It’s very simple and direct. No money is needed to reach the desired outcome.

Disadvantages

It’s extremely difficult to coordinate, and completely impractical. Someone somehow needs to find a group of people who make a “closed loop” (like our example) where everyone will be satisfied if each person passes what they have to the next person around the loop.

Even if such a group of people can be found, they need to be available to meet at the same place and time to make the trade. If just one person can’t make it (or forgets to bring what they’re trading), the meeting has to be rearranged.

People who have bought or sold a house in England1 often experience similar problems. Imagine having to go through it for grocery shopping!

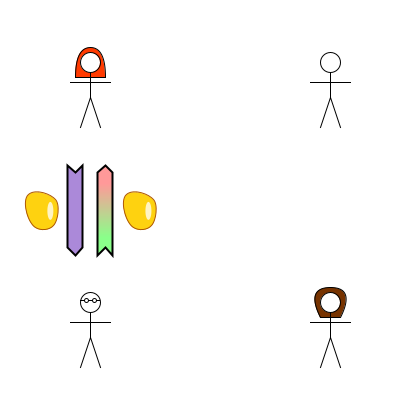

Commodity money

If there’s a certain type of good which just about everyone would agree to receive in exchange for what they have, either because they’d be happy to keep it themselves or because they are confident that someone else will exchange something valuable for it, that good can be used as a commodity money.

Let’s assume that everyone in our example is happy to trade what they have for amber. Now the problem can be solved without needing one big transaction involving 4 people. Instead, there can be 3 smaller transactions, each involving 2 people, making it far easier to coordinate.

Alice swaps her amber for Bob’s book.

Bob swaps the amber for Charlotte’s cake.

Charlotte swaps the amber for Dom’s DVD.

Each person is happy with each individual transaction. Notice that the result is exactly the same as for the “big trade”. The book went from Bob to Alice; the cake went from Charlotte to Bob; the DVD went from Dom to Charlotte; and the amber went from Alice to Dom—just indirectly this time, via Bob and Charlotte.

Advantages

The trade doesn’t need to be coordinated. Each individual transaction between 2 people leaves both of them satisfied with the result.

Instead of needing to think about prices of everything in terms of every other thing (e.g. how many DVDs would you want in exchange for one cake?), everyone can just measure prices in units of the commodity money (e.g. you’re prepared to give one piece of amber for one DVD).

Disadvantages

Commodity money can be fiddly to handle.

It doesn’t scale well to large purchases (e.g. a large building), because it’s hard to get, exchange and store enough of the commodity.

If someone suddenly introduces more of the commodity (e.g. gold from South America being brought to Spain in the 16th century), it can suddenly devalue existing money.

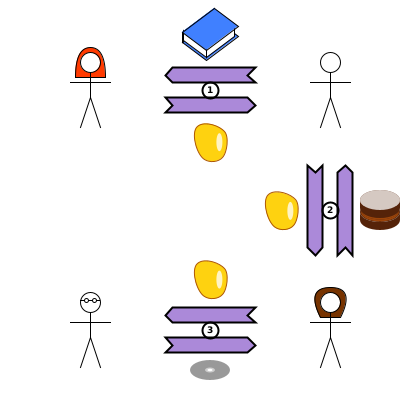

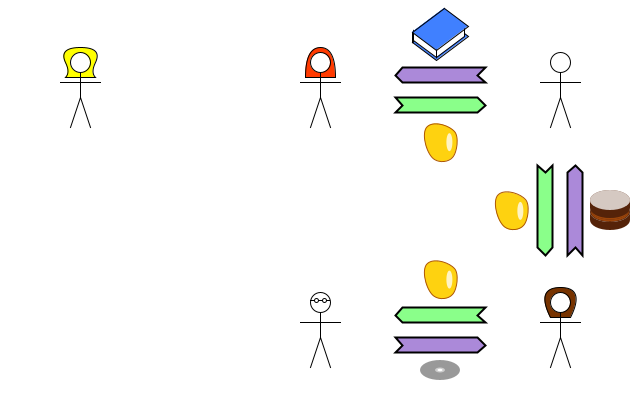

Personal IOU

Sometimes people don’t have something to sell at the time when they want to buy something.

In this case, they can get what they want by writing an IOU (creating a new debt), promising to give the other person something later. Suppose that Bob, Charlotte and Dom all know Alice well, and trust her to keep her promises. Alice goes to Bob’s bookshop, and sees that there’s only one remaining copy of a book she really wants, but she doesn’t have any amber with her. Bob might accept her promise to give him the amber next week, in exchange for the book now.

But Bob wants a cake tonight. He can go to Charlotte, and swap Alice’s IOU for a cake. Alice now owes the amber to Charlotte.

The next day, Charlotte finds out that Dom wants to swap a DVD of a film she’d like to see for some amber. Charlotte can swap Alice’s IOU for the DVD. Alice now owes the amber to Dom.

Early next week, Dom takes Alice’s IOU to her, and asks for the amber which she promised. She hands it over, and Dom agrees that the debt is no longer owed. (This doesn’t affect either person’s RNW).

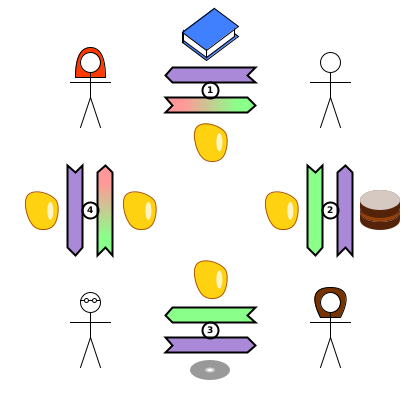

Here’s the complete diagram for the scenario.

Notice how the transfers of the tangible assets (the purple arrows on the outside) are exactly the same as in the “big trade”. The debt simply facilitated the complete 4-person transaction by making sure that each individual 2-person transaction was a fair exchange of raw net worth. The effect of the debt on each person’s RNW was temporary, and completely cancelled out over the period of its existence:

Alice’s RNW first decreased by the amber when she wrote the IOU (1), then increased again, undoing the decrease, when Dom wrote off the debt (4).

Bob’s, Charlotte’s and Dom’s RNW first increased by the amber. (Bob’s when Alice wrote the IOU (1); the others when the IOU was passed on to them (2,3)). Their RNW then decreased again, undoing the increase. (Bob’s and Charlotte’s when they passed on the IOU (2,3); Dom’s when he wrote off the debt (4)).

Advantages

People can buy something without having something tangible to offer in return at the same time.

As long as the person writing the IOU is willing and able to pay the debt, there’s no limit to how big an IOU can be written. A shop can write an IOU to a wholesaler in exchange for a huge number of goods to put on the shelves. It can pay this IOU once it’s sold them. This is incredibly useful for customers who can browse for what they want, and buy it immediately.

Disadvantages

An IOU doesn’t work as money when the debtor isn’t well known and trusted (and trustworthy). Even if someone completely trusts the debtor to keep their promise, they still might not accept it as part of a trade if they don’t think that they could use it to buy something from someone who doesn’t know the debtor.

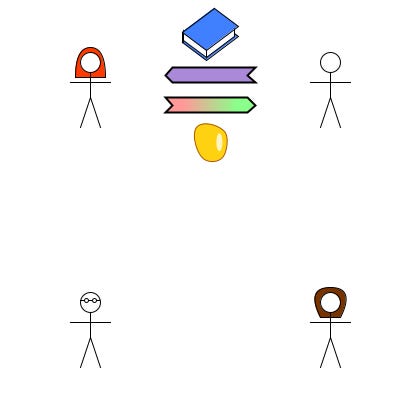

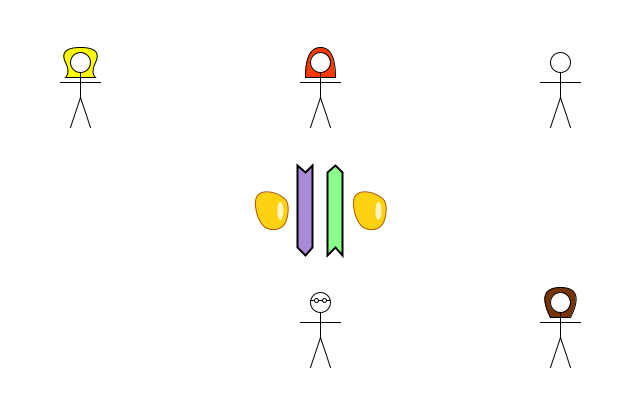

Trusted Third Party IOU

Using IOUs for trade relies on everyone knowing and trusting the person who wrote them. This could work in a small community, but is impractical even for a modest-sized town, let alone international trade. But there is a solution.

Suppose that Alice, Bob, Charlotte and Dom don’t know each other at all, but everyone knows Eve, and also knows that she is always determined and able to keep her promises, so they trust her. Imagine the same situation as for the previous approach, where Alice sees a book she wants but doesn’t have any amber with her.

Bob won’t accept a personal IOU from Alice in exchange for the book, because he doesn’t know if she’ll pay, and even if he is confident, he doesn’t think that Charlotte will swap Alice’s IOU for a cake. But fortunately, Eve is also in the bookshop. Alice asks Eve if she can help out, and Eve agrees to write Alice an IOU for some amber if Alice writes an IOU to Eve for the same amount of amber.

Now the problem is essentially solved. Everyone trusts Eve’s IOU, so Bob will swap the book for it, Charlotte will swap the cake for it, and Dom will swap the DVD for it.

Finishing off is slightly more complicated than for Alice’s personal IOU. First, Alice meets Dom and swaps her amber for Eve’s IOU.

Alice still owes her debt to Eve, but she’s now owed the debt by Eve again. Next time she meets Eve, they both agree to write off the debt owed to them by the other.

Once again, we’re left with the same result as the “big trade”. This time there were two new debts, both of which were used for temporary transfers of RNW. The transfers of tangible assets were exactly the same as in all the other solutions.

Advantages

All the advantages of personal IOUs, plus you only need a few trusted and trustworthy people whose IOUs circulate as money.

Disadvantages

If trust in someone like Eve is misplaced because she can’t keep her promises, a lot of people who thought they were going to get something appropriately valuable in exchange for their IOU may get less than they expected (perhaps nothing) when they write off the debt. What they believed had been an exchange with a buyer turns out to have been just a donation to them.

What was Eve doing?

Eve is a bank. The IOU she wrote to Alice is generally accepted by people as payment for things. It’s a debt which people use as money. Creating this money doesn’t increase Eve’s RNW: it actually decreases it, because it’s her liability. The reason that she is happy for her RNW to decrease in this way is that she gets an IOU from Alice in exchange, which increases her RNW, undoing the decrease.

Summary

We’ve seen a few different ways to solve the problem of people wanting to exchange things they have for things they would prefer to have. Whether or not these different approaches have been used in history is up to historians to discover. But the One Lesson shows that they can work, and there’s nothing inherently fraudulent about it, as some people allege. In each case, people are swapping some of their RNW for what they consider a fair quantity of someone else’s RNW.

The approaches which use debts only work in a society where debts are generally paid. Trust, and more importantly trustworthiness, are essential to a modern, efficient economy.

Probably lots of other places too.

For the record, I note that Eve doesn't charge Alice interest on her "loan" of credit. That's not a real bank "loan".