In the last post, Eve, a trustworthy person who is trusted by everyone, acted as a bank by swapping new IOUs with Alice. This allowed Alice to spend Eve’s trusted IOU, when Bob wouldn’t accept Alice’s personal IOU as payment for a book.

In this post, we’ll look a bit more closely at the main things a bank does, and what charging interest on loans is about. For now, we’ll carry on assuming that the community uses amber as their main type of money (and happily accepts IOUs for amber from a trusted bank as a substitute).

Some jargon

Before we go further, it’s time to introduce a curious bit of jargon. We’ve seen that when a bank lends, there are two new debts. These have names:

The debt owed by the bank to the borrower is called a deposit. (Also known as a demand deposit).

The debt owed by the borrower to the bank is called a loan.

These seem like terrible names, because they’re so different from everyday use. People think of a deposit as cash handed to the bank in exchange for the bank’s IOU, and talk about “getting a loan from the bank” as though the loan is what the bank transfers to them. Unfortunately, these terms are so entrenched, I think we’re stuck with them. But you’ll get used to them.

Bank transactions

Here are all but one of the main types of transaction of a simple bank. Look at each diagram carefully, and make sure you understand exactly how everyone’s assets and liabilities change in each transaction. (See the post on the 7 economic actions if you need a reminder). Also, see if you can spot something the transactions all have in common—look at how everyone’s raw net worth changes.

New loan

Alice doesn’t have amber at the moment, but she wants to buy a book. She goes to the bank for a loan of 1 piece of amber.

As before, Alice and the bank create new debts to each other: the loan (top) and the deposit (bottom).

Transfer Deposit

Alice buys a book from Bob by using her debit card. She’s instructing the bank to transfer her deposit of 1 piece of amber from her account to Bob’s account.

Alice writes off the bank’s deposit, and the bank creates a new deposit for Bob. (The overall effect is to transfer 1 piece of amber from Alice’s RNW to Bob’s. The bank’s RNW doesn’t change because it both increases and decreases by 1 piece of amber).

Close loan

Suppose Alice sells something, and in exchange gets a deposit for 1 piece of amber.

Now she can repay the loan, as we see below.

Alice and the bank, owing each other 1 piece of amber, agree to write off the deposit and the loan simultaneously.

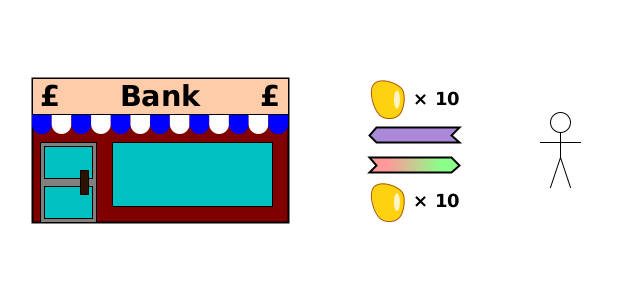

Deposit

Bob has 10 pieces of amber, but doesn’t want to carry them around. He deposits them at the bank.

Bob transfers 10 actual pieces of amber to the bank, and the bank creates a new deposit (a new debt to Bob) for 10 pieces of amber. (Bob’s bank account now has 10 more pieces of amber than before).

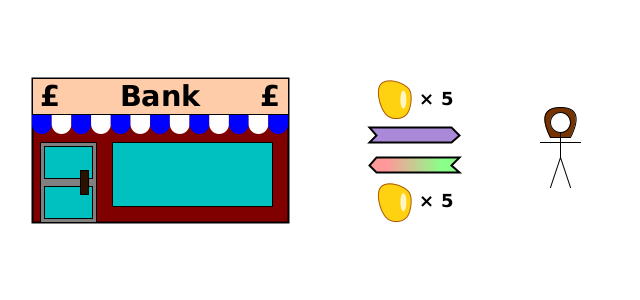

Withdrawal

Charlotte has a deposit of 20 pieces of amber (i.e. the bank owes her 20 pieces of amber). She wants 5 actual pieces of amber, so she withdraws them.

Charlotte goes to the bank, and agrees to write off 5 pieces of amber owed to her (reducing her account balance by 5) when the bank gives her 5 pieces of amber from its vault.

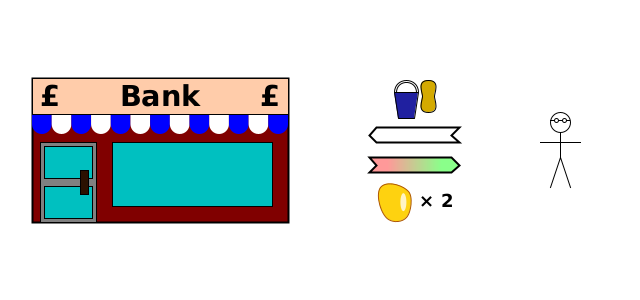

Buy services & consumable goods

Dom washes the bank’s windows. The bank pays him 2 pieces of amber in the form of a bank deposit.

The bank creates a new debt owed to Dom in exchange for his service. (His account balance increases by 2 pieces of amber).

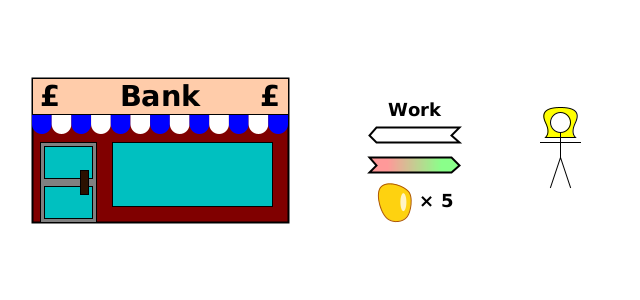

Pay staff

Eve works on the tills for the bank. At the end of the week, the bank pays her by creating a deposit for her (adding 5 pieces of amber to her account).

The bank creates a new debt owed to Eve in exchange for her service. (Her account balance increases by 5 pieces of amber). Notice how this is just like Dom above.

Borrower defaults

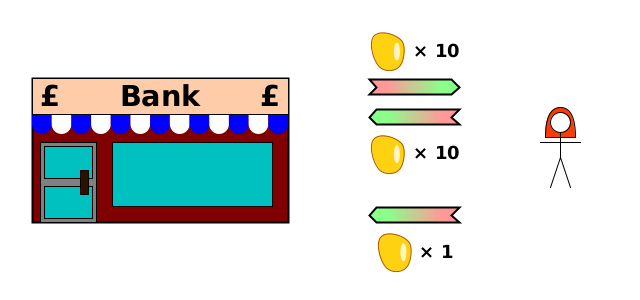

Suppose last year, Frank borrowed 10 pieces of amber from the bank, but spent it all on cakes and ate them. He has no other assets, so can’t pay the bank what he owes it.

He goes through bankruptcy, in which all his debts, including the one owed to the bank, are forcibly written off. Here’s how it affects the bank:

The bank simply has to write off the loan debt owed by Frank. The deposit which it created when it made the loan still exists, but it’s currently owed to the cake maker. Unlike with a loan repayment, the deposit debt isn’t written off at the same time: this is a transfer of RNW away from the bank, not an exchange.

What’s Missing?

The thing to notice is that every transaction above either leaves the bank’s RNW unchanged, or reduces it. The bank is becoming worse off over time. Why would anyone set up a business to provide a useful service if they’re going to make a guaranteed loss?

Banks need some sort of income for their service. One possibility is charging an annual fee for having a bank account, but far more common is to charge interest on loans. For every day that someone has a loan from the bank, a percentage of that amount is added to the amount they owe to the bank. In order for the bank to continue to operate, the interest received must cover at minimum:

The costs of running the business (staff wages plus services, and consumables like electricity and paper), and

The losses from defaults.

So when a bank lends, the borrower also agrees to pay a certain amount in interest in the future: this is an additional debt owed by the borrower to the bank. Here’s a simple example of a bank lending and charging interest1.

Bank profit or loss

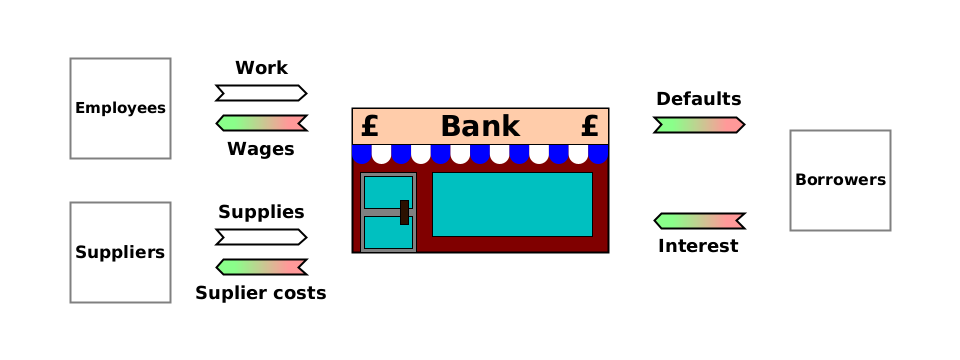

The diagram below only includes those transactions which change the bank’s RNW (so not including new loans, closing a loan, deposits, withdrawals, or transfers). This shows how it makes a profit (or loss).

The services2 don’t affect the bank’s RNW. So the only changes to the bank’s RNW are:

Decreases (wages, supplier costs and defaults); and

Increases (interest).

The bank’s profit is therefore: interest payments minus wages minus supplier costs minus defaults. The skill in banking is charging enough interest to not make a loss (and preferably make a profit), but not so much that borrowers go to their competitors for their loans instead.

Summary

Banks provide a useful service by allowing people to use the bank’s trusted IOUs for their spending. Providing this service isn’t free for the bank: it must pay staff and suppliers, and sometimes borrowers fail to repay their loans. Banks need some sort of income, and the most common approach is charging interest on loans.

As long as the bank’s income from interest payments is at least as much as the running costs of the bank plus the losses when borrowers default, the bank can continue to operate.

This is a loan which is paid back at a fixed time. Interest on a more flexible loan would be a series of contingent debts, which become actual debts if the loan hasn’t been repaid by a certain time.

Suppliers provide consumable tangible assets too, but because they are consumed quickly, we can ignore the temporary short-term increase they give to the bank’s RNW.

I like your pink-green-purple-white arrow system, which incorporates the double-entry accounting concepts (pink-green) used by Richard Werner.

Don’t compromise your system's usefulness by accepting banker’s jargon on “deposits” and “loans”. Sloppy definitions belong in Wonderland, where words mean whatever Humpty Dumpty says they mean. Be precise, and accurate as well. I call their jargon words "Trojan Mind-worms". If you “stick with” them, I'm afraid you will have fallen for one of their “magical deceptions”.

Also, I think you need to include in your repertoire the simple accounting fact that it’s not possible to “lend a liability” the way you can lend an asset. Even the Bank of England admits this fact, which is the subject of my article #4 The Bank of England exposes the illusion of bank "credit-lending" (substack.com).