Money and Banking (4)

Does charging interest on loans make it impossible for some borrowers to pay?

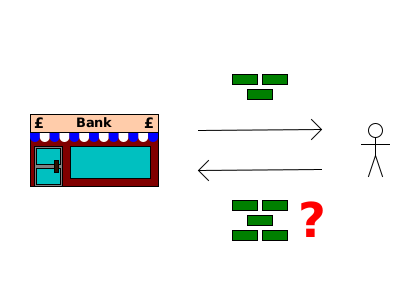

Have you heard it said that if banks ever charge interest, there’s never enough money in the economy for all borrowers to repay their loans with interest?

A lot of people believe this. Their reasoning goes something like this:

Money’s only created when banks lend, and they only create enough money for the borrower to repay the principal (the amount originally lent) and none for the interest. The money used to repay the principal is destroyed1. For the borrower to pay the interest, more money has to be created, so there needs to be a second person borrowing from the bank, who can buy something from the first borrower. But now there isn’t enough money for the second borrower even to pay the principal of their loan, let alone the interest, so they need a third borrower to borrow even more, and so on. The amount of borrowing has to increase exponentially, and when nobody is prepared to borrow any more, someone (or lots of someones) will be left with a debt they have no way of paying.

I first came across this claim in the film Money As Debt early in 2008, and I set out to discover if the claim was true. In fact, I found:

It’s not true;

It’s not even true that banks only create money when they lend; and

I’d discovered an apparently new way to understand economics, which I now call the One Lesson2.

Here’s how I worked it out. The details are important, so do make sure you understand exactly what’s happening in every step.

Testing the idea

Instead of trying to understand the whole economy at once, where it’s too easy to make wrong assumptions, it’s far better to start with a much simpler problem. So instead I tried to find the smallest step-by-step scenario where:

Someone borrows from a bank,

They use the (newly-created) money for a useful purpose,

They finally repay the loan with interest, and

Everyone ends up clearly better off than they were at the start.

If I could find any scenario like this, I’d have proved that the Money As Debt claim was wrong, and that banks charging interest doesn’t automatically lead to unending growth in lending.

Here’s what I came up with.

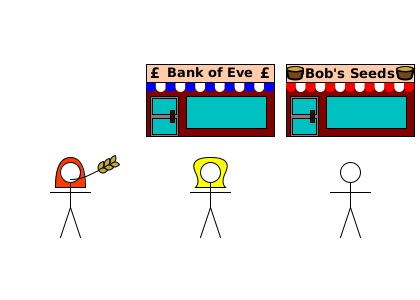

Alice is a farmer. Eve has a bank. Bob sells seeds.

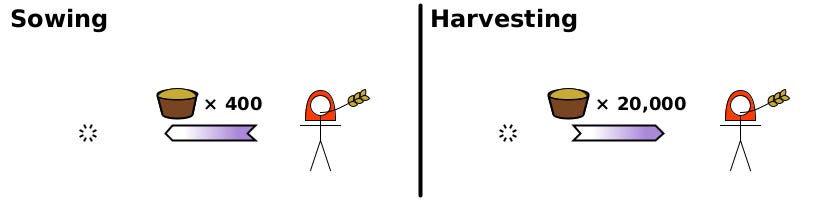

Alice has plenty of land, but only has enough wheat seeds to plant half of her farmland. She also doesn’t have any money.

Alice asks Bob if he’ll sell her some seeds in exchange for her personal IOU for some of the harvest. But Bob doesn’t want to, because he knows that if Alice’s harvest fails, all he’ll be able to get is some of her farmland, and he doesn’t want that. If he can’t get paid in wheat, he’s only interested in getting a car.

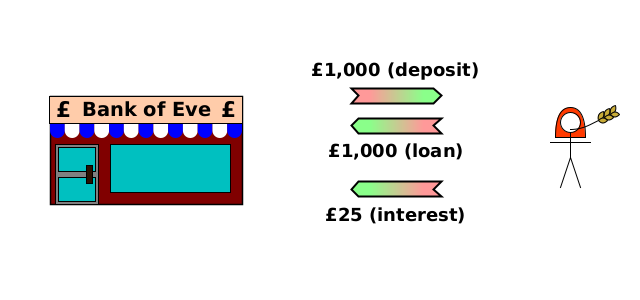

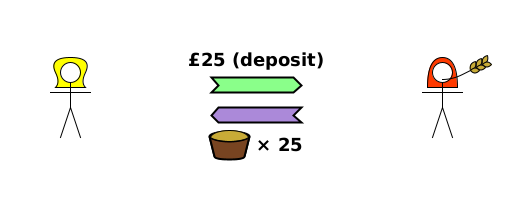

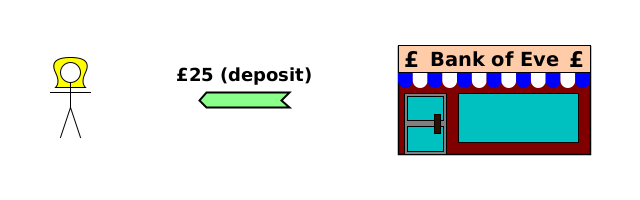

Eve actually has a spare car, and she’d be prepared to exchange it for £1,000 if Bob can’t use it to buy wheat. So Alice borrows £1,000 from Eve’s bank at a 5% (annual) interest rate, to be repaid after 6 months. (So she’ll pay £25 interest).

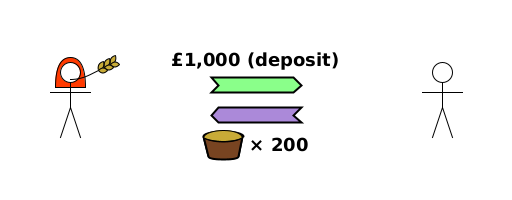

She then buys 200 bushels3 of wheat seeds from Bob for £1,000.

Alice can now sow all of her farmland. And after 6 months, Alice harvests 20,000 bushels of wheat seeds.

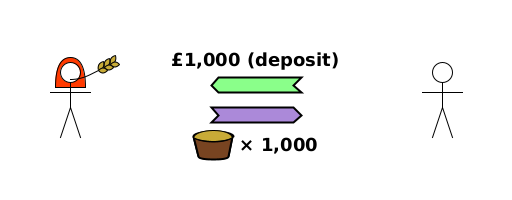

Alice now sells 1,000 bushels of wheat to Bob for £1,000. (Bob has to sort it into 200 bushels which can be sold for sowing, which restores his stocks, and 800 bushels which he can mill to make bread).

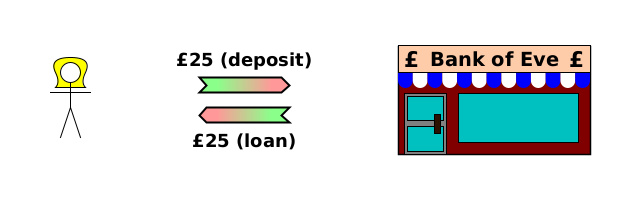

Alice pays the £1,000 principal to Eve’s bank. This is a mutual write-off of debts.

But now she seems to be stuck: all the money was destroyed when Alice repaid the principal, so apparently there’s no way for Alice to pay the interest.

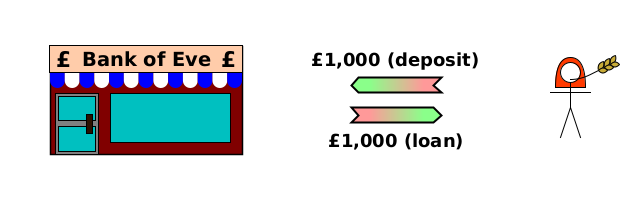

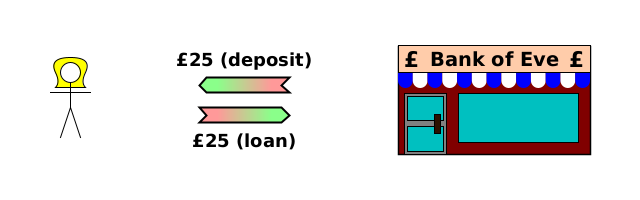

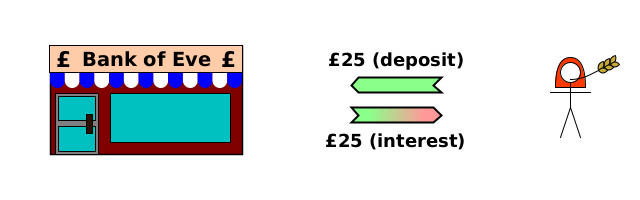

This is where I had a breakthrough in my thinking. Even if the Money As Debt film were correct, and money is only created when a bank makes a loan, Eve can tell her bank to lend £25 to Eve herself — without charging any interest. So that’s what happens.

Eve now buys 25 bushels of wheat from Alice for £25.

Alice now has money, so she can pay the interest to the bank.

Eve instructs her bank to pay her a £25 dividend.

Finally Eve uses the £25 to repay the principal of her interest-free loan.

There is now no money again, but everyone is definitely better off than they were at the start:

Alice has 18,775 extra bushels of wheat (20,000 - 1,000 - 25 - 200).

Bob has 800 extra bushels of wheat.

Eve has 25 extra bushels of wheat.

Nobody is in debt.

This is completely sustainable. The same sequence can happen year after year with no debts accumulating, because all debts are discharged by the end of the year.

What this proves

This sequence proves that banks charging interest can be sustainable, and doesn’t require an exponential growth in lending, with someone inevitably defaulting at the end. That’s a very important result, because many people claim that charging interest inevitably leads to some people being unable to pay their debts to banks.

It doesn’t mean it’s impossible for the people who control banks to force some people to default by accumulating debts owed by borrowers and refusing to spend anything. That definitely could work if there’s a banking monopoly or cartel which “corners the market” for money. But it’s not clear to me that it would work in a competitive banking system — I suspect not, but I haven’t reached a final conclusion. If you have any thoughts, please leave them in the comments.

Summary

Banks charging interest doesn’t automatically lead to ever-increasing debt and defaults. The above counter-example proves this.

In fact the money used to pay the interest is typically destroyed too, but we’ll pretend it isn’t because that’s what people who make this argument usually say.

The “One Lesson” is: To understand economics, look at how each decision or action affects each person’s Raw Net Worth (RNW). A person’s RNW is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

A bushel is a standard-sized basket, and unit of measure. It apparently holds enough wheat seeds for roughly 50 loaves of bread.

Re footnote 1: “interest paid” on a bank loan is not “destroyed”; it sticks to the banker’s fingers, like the 25 bushels of wheat that end up in Eve’s hands in your scenario.

Alice may have had her loan interest offset by Eve’s purchase of wheat, but she ultimately paid the bank’s interest with wheat worth £25.

I don’t believe a real bank would allow Eve to do what you propose. In the end, she seems to have extracted 25 bushels of wheat from the economy without paying for it.

As I summarise the outcome of your scenario, Eve spent the bank’s profit (her £25 dividend) to repay the interest-free loan she used to buy £25 worth of Alice’s wheat, so that Alice could pay the £25 interest on the £1,000 loan from the bank, thus replacing the “profit” previously extracted by Eve as a dividend.

Do you mean that the bank [Eve] gave Alice the £25 so she could pay the bank the £25 interest she owed it? And did that £25 come out of the bank’s “equity”?

If so, that would mean “everyone is definitely better off” except the bank, which won’t survive if Eve’s malfeasance persists. Does Eve go to jail for snaffling £25 of bank equity under false pretences?

On reflection, your “breakthrough” doesn’t prove “that banks charging interest can be sustainable”. It sounds more like the perfect argument for ABOLISHING interest charges on all loans of credit – and jailing self-serving, sociopathic bankers.