Do banks only create money when they lend?

In the last post, I wanted to show that even if this is true1, it’s still possible for banks to charge interest and for everyone to successfully pay their debts to banks. The ‘trick’ to this was a slightly fiddly roundabout process involving the bank lending to the shareholders:

The bank lends interest-free to the shareholders — creating new money.

The shareholders transfer this money to the borrowers (maybe buying something).

The borrowers use the money to pay the interest.

The bank pays a dividend to the shareholders.

The shareholders repay their debt to the bank.

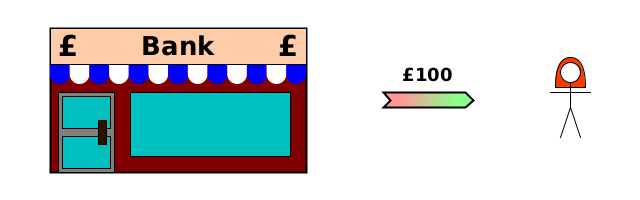

But this trick isn’t actually needed at all. Banks can create money simply by increasing the balance of a customer’s account. It’s a “create debt” action, which transfers some of its Raw Net Worth2 to the customer (its liabilities ↑ and the customer’s assets ↑).

So we don’t need the full 5-stage process above. We only need these 3 actions:

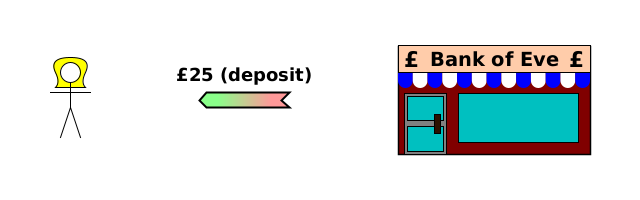

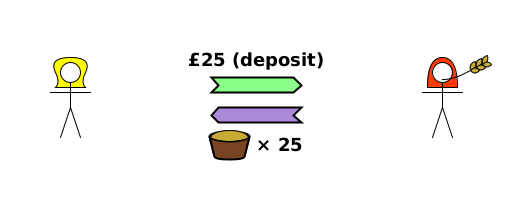

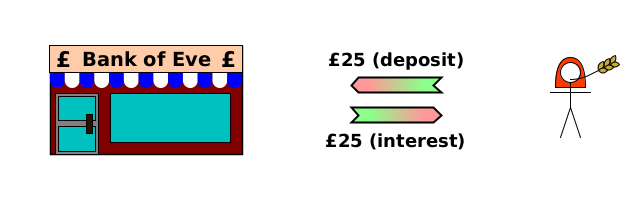

The bank pays a dividend to the shareholders (which creates money).

The shareholders transfer this money to the borrowers (maybe buying something).

The borrowers use the money to pay the interest (which actually destroys the money).

The outcome is identical to the 5-stage process. It just means that the shareholders don’t have to borrow interest-free from the bank and then repay it.

Does paying interest really destroy the money used?

If you examined the diagrams above carefully (and I hope you did!), you’ll notice that when the bank pays a dividend, it’s creating new money (pink-to-green arrow), not passing on existing money (green arrow). And when Alice pays her interest, the money she uses is destroyed (green-to-pink arrow). This is different from what we saw in the last article, where I was pretending that the “Money As Debt” film was right about when money is created and destroyed3.

In fact, there aren’t any special rules about when money is created and destroyed. Like any debt:

If you pay someone with their own IOU, it gets destroyed. This is a write-off debt action. (Green-to-pink arrow. Your assets ↓, their liabilities ↓)

If you pay someone with a third party’s IOU, it continues to exist. This is a transfer debt asset action. (Green arrow. Your assets ↓, their assets ↑).

(A borrower could actually pay their principal or interest debt to a bank using cash. Since this is a liability of a third party (the central bank), the money wouldn’t be destroyed in this case. It would just be transferred to the bank to put in their tills or vault).

Can a bank really create money whenever it wants?

Lots of people continue to claim that banks can’t create money without lending. Some think that it would be illegal for a bank to simply create money, and I can only assume that most of these think that the bank would be getting something for nothing. But it’s the exact opposite: creating money decreases the bank’s RNW, because doing this increases its liabilities without changing anything else. The key to understanding our monetary system is that we use the IOUs of banks as money.

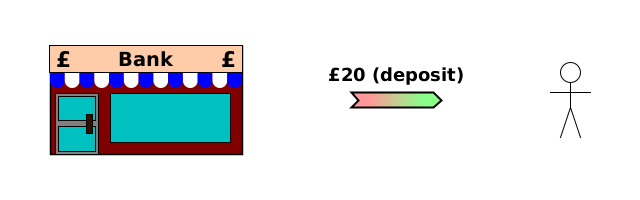

Nobody’s ever given me an argument which I find convincing for why banks can’t simply create money4. When I opened my first account as a new student, the bank gave me a starting balance of £20 as an incentive for choosing them over other banks. It did this by increasing the balance on my account, just like in the first diagram above.

I don’t think I’ve ever come across anyone who believes that a bank couldn’t have decided to give me £20 cash from one of its tills as an incentive payment. But what if I’d then deposited the cash in my new account at the bank?

Transaction 1 is the bank giving me £20 cash. Transaction 2 is me depositing the £20 cash at the bank: I give them the cash (green arrow), and they promise to pay me later (pink-to-green arrow). The cash would go from the bank to me, and back again, ending up exactly where it started. Because the two green arrows cancel each other out, the result would be identical to the bank simply increasing my bank balance by £20.

How could short-cutting the process by not bothering to transfer cash to me and back again possibly make it illegal?

The same applies when a bank pays wages to an employee, or pays a supplier who banks with it. The bank can simply increase the balance in the employee’s/supplier’s account, instead of paying them cash and having them deposit the cash back with the bank.

Summary

Banks can create money simply by increasing the balance in a customer’s account. It decreases the bank’s RNW and increases the customer’s RNW.

If the bank is a limited company, its equity (i.e. what it owes to the shareholders) decreases by the same amount to compensate, so it’s actually just transferring some of the shareholders’ RNW to the customer — via the bank.

It’s not!

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

It implies that money is only destroyed when the principal of a loan is repaid, not when interest is paid.

Creating money is simply a transfer of RNW from shareholders (their equity stake ↓) to a customer (their assets ↑). But this is only fine as long as the bank actually has enough equity, otherwise it would become insolvent, meaning that it doesn’t have enough assets to pay all of its creditors.

![[1] (TD) Bank→Me {£20 (cash)}. [2] (TD) Me→Bank {£20 (cash)}; (CD) Bank→Me {£20 (deposit)} [1] (TD) Bank→Me {£20 (cash)}. [2] (TD) Me→Bank {£20 (cash)}; (CD) Bank→Me {£20 (deposit)}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F210b8869-5307-4f42-8b2b-9d610a4e567d_640x300.png)

When you say, “… creating money decreases the bank’s RNW, because doing this increases its liabilities without changing anything else”, you are visualising <money> creation as a one-arrow transaction.

I agree that a bank’s main profit-earning business is creating new <bank liability> IOUs which customers can use as <money>, but it (almost) always does it in *response* to the creation of a new <debit item> in its asset account, caused by a customer’s deposit of <something valuable>, like a <£200,000 promissory note> [or a £20 note].

Your one-arrow idea represents only two items from a four-item accounting record involving two different balance sheets. An arrow pointed in one direction could represent EITHER the customer depositing its IOU at the bank, for example, OR (in the other direction) the bank responding with its <credit> IOU obligation to the customer. Without a second arrow, you have either the “unfinished business” of the customer’s IOU deposit, or an “unrealistic image” of a bank wantonly giving away its <credit> IOU for no reason, both of which I call “one hand trying to clap”.

Creating <money> does increase the bank’s liability each time - by the amount of the new <credit> it creates – as you say. But it does that in response to a matching increase in its assets – usually by the amount of the <debit> the customer’s deposit creates. It’s not a one-sided increase (in liability), it’s two-sided - as you’d expect in a *double-entry* accounting system - and it has *two* participants with *opposite* (balance sheet) perspectives.

What you draw from Frances Coppola’s coffee machine story is tainted, as explained in a previous comment. It seems she has misled you to your one-arrow description of <money> creation by a bank. Let her go and focus on evidence; thought experiments and “models” are wide open to “undetected” errors.

I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news (again), but your ‘simplified’ model goes off the rails at (new) step “1” and never recovers. No <money> is created in any of the cases where you claim it is.

I’m NOT saying <money> CAN’T be created when and how you say it is INSIDE your model! You are the supreme authority in that world. When you say, “Jump!”, Eve can only ask, “How high?” and WILL rise 200 feet in the air when you COMMAND her to. If you don’t COMMAND her to come down, she can even stay up there indefinitely.

Reality doesn’t work that way, and any reputable accounting website would have revealed the following accounting facts: bank shareholder dividends, bank employee wages/salaries and external suppliers to a bank are ALL paid out of a bank’s “existing funds”, as follows:

(i) Shareholder dividends: typically drawn from profits;

(ii) Employee salaries/wages: typically drawn from operating income; and

(iii) External supplier costs: typically drawn from cash reserves or operating income. [Source: Microsoft Copilot.]