When you spend a long time studying something, and finding what seems to be an important discovery, it feels for a while like the job is mostly complete. All you need to do is tell people about it, or maybe write about it in an academic journal (or on Substack if you don’t have the PhD which will get you taken seriously by the journals), and if you’re right that your discovery is true it should be widely accepted pretty quickly.

No such luck, it turns out. There are lots of possible reasons for this; one reason which has become obvious to me when I’ve been trying to share the ideas of the One Lesson on social media (mostly X) is that people seem to be trying to fit it into their current understanding to see if that makes a useful hybrid (and usually finding it doesn’t), rather than treating it as a completely new way of thinking about economics.

So for example, when I say that creating money (see diagram below) is an action which decreases the issuing bank’s raw net worth1, which by itself shows a potential problem, many economists simply don’t see the issue. They’re used to thinking that the only possible problem with creating new money is that it might cause inflation, which is a much more complicated idea — not just how expensive things are, which is complicated enough, but how quickly those prices are increasing. In a similar way, some even think that a Ponzi scheme is actually fine right up to the point when it first defaults on a debt, while the One Lesson shows that it’s already failed as soon as it first promises to give back more to one of its “investors” than it received from them (unless it somehow finds another way to make a profit) — it’s just that it hasn’t been noticed by everyone yet.

A good friend of mine from my university days, Martin, was one of the first to see the significance of the One Lesson. He’s a far better communicator than I am, and he says that I need to help people to “locate” this new approach — work out how it fits with their existing understanding. That’s what I’m going to try to do here.

Like Newton’s laws

I think it’s best to think about the One Lesson as being the economics equivalent of Newton’s laws of motion. Before Newton published them, people knew a lot about how things move in different situations, using a combination of experience, rules of thumb, and mathematical formulas which seem to work quite well in particular situations. What Newton did was to find some rules which are incredibly simple, and always true2 — whether it’s for an apple falling off a tree, the flight of an arrow, a cart being pulled by a horse, or the planet Jupiter orbiting the Sun.

Because Newton’s laws are always true, they give us an independent way to check the results of our other ways of thinking. If they predict a different outcome, it’s most likely because we’d made some wrong assumptions, or the rules of thumb or formulas weren’t quite good enough. And, as we’ll see, the One Lesson does the same for economics. Let’s compare them to see how strong the analogy is.

Basic ideas

For Newton’s laws, the basic ideas are:

Physical objects exist.

Each physical object has a momentum (its mass3 × its velocity4).

Forces5 exist which can act on (i.e. push or pull) physical objects.

And for the One Lesson:

People6 exist.

Each person has a raw net worth (their assets - their liabilities).

Actions7 exist which change people’s assets and liabilities (and therefore RNW).

The laws

Newton had 3 laws of motion. The first is actually just a special case of the second.

If there’s no force acting on an object, it continues to move at a constant velocity.

If a force acts on an object, its momentum changes at a rate directly proportional8 to the force. (In the most common case where the object’s mass doesn’t change, the force equals its mass times its acceleration9:

F = ma).For every force acting on one object, there is an equal and opposite force acting on another object. (So if Alice and Bob are standing facing each other on an ice rink, and Alice pushes Bob, he’ll go sliding backwards, but so will she — in the opposite direction).

From these laws, a mathematician can fairly easily work out that the total momentum of a group of objects is constant — as long as no forces are applied from outside the group. All that can change is how that momentum is distributed between the different objects.

We could write some equivalent laws for the One Lesson, following a similar pattern.

If there’s no action involving a person, their RNW doesn’t change.

If an action involves a person, their RNW decreases (if assets↓ or liabilities↑) or increases (if assets↑ or liabilities↓) by the asset or liability associated with the action.

Apart from production and consumption actions, for every change in one person’s RNW, there is an equal and opposite change in another person’s RNW. (This is summarised in the table of the 7 economic actions here).

(Production actions increase one person’s RNW without decreasing another person’s, and consumption actions decrease one person’s RNW without increasing another person’s).

From these laws, a mathematician can fairly easily work out that the total RNW of a group of people changes in a period of time by how much they have produced in that time minus how much they have consumed in that time — as long as there are no actions involving both someone in the group and someone outside the group.

This is slightly more complex than Newton’s laws: momentum is conserved, but RNW can increase or decrease depending on how much production and consumption takes place. Even so, it’s still quite easy to understand.

Linearity!

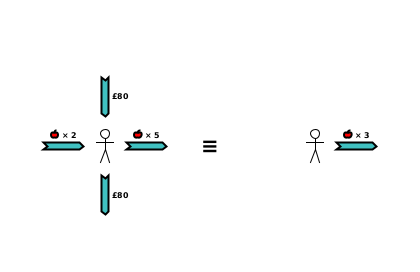

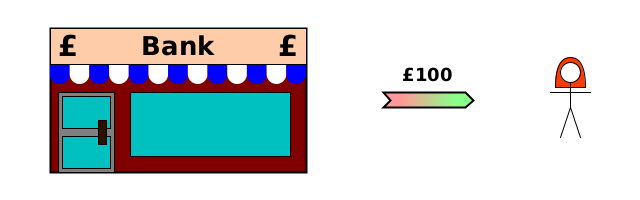

One of the most important features of both Newton’s laws and the One Lesson is that they are both linear. That means that the change to each object’s momentum when multiple forces act on it is the exact sum of the changes to its momentum from each of the individual forces.

And the effect on each person’s RNW of multiple actions is the exact sum of the effects of each individual action.

(Note: These blue arrows represent actions of any type — production, consumption, creation of new debt, etc. The effect on RNW is always the sum of the effects on RNW of the individual actions).

What this means is that, like Newton’s laws, the One Lesson is a completely rigorous macroeconomic model, based on some incredibly simple ideas. Just as Newton’s laws give us an independent way to check whether other theories of motion are correct, the One Lesson gives us an independent way to check whether other theories of economics are right.

If a different theory of motion says that it’s possible to change the total momentum of a group of objects (without an equal and opposite change to the momentum of the objects outside the group), then unless Newton’s laws are wrong, the error must be in the other theory — probably because it’s using some invalid assumptions.

In the same way, if a different theory of economics says that it’s possible to increase the total RNW of a group of people without them having to produce more than they consume (and without decreasing the RNW of the people outside the group), then unless the RNW model is wrong, the error must be in the other theory — again probably because it’s using some invalid assumptions.

In my experience, the usual invalid assumption turns out to be that creating a new debt increases total wealth because it increases one person’s assets. What that ignores is that it also increases someone else’s liabilities. Some economists try to argue away the significance of increased liabilities, perhaps because it’s the government taking them on, and “governments can never run out of money”, but that is to miss the point that its RNW can certainly decrease, and it can even end up without enough assets to settle all of its liabilities. To understand why this is important, see this earlier post on insolvency being unassigned losses. There can be no doubt that creating a new debt just transfers some of one person’s RNW to another person’s, so it’s a zero-sum action.

Summary

While there are some differences in the details, the general structure of the One Lesson closely matches the structure of Newton’s laws of motion. Just as Newton’s laws make motion understandable in terms of some simple ideas (forces and momentum), the One Lesson makes economics understandable in terms of other simple ideas (actions and RNW). They are both linear and so work at both small and large scales, and they can both be used to provide a completely rigorous and independent check on other theories.

As with Newton’s laws of motion, it’s a mistake to try to create a hybrid theory between the One Lesson and other theories. Instead the right thing to do is to analyse economics using the One Lesson by itself. If the results differ from other theories, the One Lesson can help to identify the reason why. In my experience it often reveals some invalid assumptions made by other theories.

If you’re new to the One Lesson, and you’d like to understand it a little better, take a look here for a 15-20 minute introduction.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

OK, not including when things are extremely small or are moving at near the speed of light, but these weren’t discovered for another 300 years.

The number of kilogrammes (kg).

Its velocity is a combination of its speed (e.g. in miles per hour or metres per second) and its direction of travel.

Measured in Newtons (N), and associated with a direction in which it is pulling or pushing.

When I say “people”, I mean either actual human beings or corporations. Basically whoever or whatever can own things, be owed things or owe things. This includes governments, not-for-profit firms, trusts, etc.

Produce, consume, transfer tangible asset, create debt, transfer debt asset, transfer liability, write off debt.

So a force twice as strong makes the object’s momentum change at twice the rate.

Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity. For example, if a car can go from 0 to 60mph in 10 seconds, its average acceleration is 6 mph per second. In science, acceleration is usually measured in metres per second per second.

![[LEFT] Car has multiple forces acting on it: 2N left, 5N right, 80N up, 80N down. [RIGHT] Resultant force on car: 3N right. [LEFT] Car has multiple forces acting on it: 2N left, 5N right, 80N up, 80N down. [RIGHT] Resultant force on car: 3N right.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd91ac590-af22-4ff9-bcb6-a829fcd3291c_800x200.png)

![[LEFT] Bob has multiple actions involving him: gain 2 apples, lose 5 apples, gain £80, lose £80. [RIGHT] Resultant action: lose 3 apples. [LEFT] Bob has multiple actions involving him: gain 2 apples, lose 5 apples, gain £80, lose £80. [RIGHT] Resultant action: lose 3 apples.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fae73c040-a5d1-46e2-b45f-389c99eb30d2_960x400.png)

In “Money and Banking (2)” [July ‘23], you depict a bank “loan” using TWO “amber-debt” arrows pointing in opposite directions [https://www.economics21st.com/i/133430487/new-loan], which proves such a “jargon loan” process doesn’t create “new money”. That process is often called “credit creation”, but such “credit” (which you show as a pink-green arrow for “Bank owes amber to Alice”) is often confused with “money” (which is “notes and coin”) shown as “amber” in your models.

Nevertheless, in agreement with Prof. Perry Mehrling’s description of all such “jargon loans”, your 2023 article correctly showed a “bank loan” as “a swap of equal IOUs”, which belies the name “loan”; swapping “£100 in one form” for “£100 in a different form” is NOT a “loan”, it’s a “swap”.

So, what is the contradiction I mentioned in my previous comment? This present article allegedly describes “[a] bank creating money for Alice” and contains at least three errors that I can see, viz.: (1) the claim the bank is “creating new money”, and in so doing; (2) “decreases the issuing bank’s RNW”, while (3) your diagram shows the bank promising (or owing) Alice “£100” for nothing in return (L>R arrow; “Bank owes £100 to Alice”).

The errors are: (1) the issuing bank doesn’t create £100 in “new money” (amber), it creates a “credit balance in its liability account” (a green-pink arrow representing the “£100-worth” of amber the bank owes to Alice); (2) in so doing, it not only incurs a new liability (L>R arrow: “Bank owes £100 to Alice”), but also gains Alice’s promise to pay the bank, an equal new asset (L<R arrow: “Alice owes Bank £100”), so its RNW remains *unchanged*; and (3) the “issuing bank” is missing its second (L<R) arrow.

Newton would not make such mistakes. The bank's RNW would decrease if the bank gave Alice a £100 note or simply credited her account with £100 as a gift, and neither is implied by your pink-green arrow labelled “£100”, or occurs in real life.

Will your notation become an economic equivalent of Newton's laws of motion?

It may reach that point one day, and you might hasten that day if you drop the “curious … jargon” bankers have entrenched in the common language. For my money, if you don’t, it won’t.

For example, your description of banking as “creating money” contradicts your earlier article on “Money and Banking (2)” [July ‘23].