In the last post, Alice set up a Ponzi “investment” scheme in January 2000, in which she promised to pay “investors” double what they “invested” 1 year later. The money coming in wasn’t spent on equipment for producing anything, or even used to speculate (trying to buy something at a lower price and sell it at a higher price). Instead, she just paid the earlier “investors” from the money coming in from new “investors”.

As with all Ponzi schemes, after she ran out of new “investors”, existing investors found out that they weren’t going to receive what they were promised. In this case, in January 2002, Dom was expecting Alice to give him £1,000, but she could only give him the £100 she had left: £900 less than she promised, and £400 less than he’d originally “invested”.

It took 2 years for it to become impossible to ignore that Alice’s scheme had failed. But could people have known that it was doomed to fail beforehand? Was it inevitable?

Insolvency is the problem

The answer is, essentially, yes, it was inevitable1. We assumed Alice had no other assets (or liabilities) to start with. Because of this, the scheme failed as soon as Alice promised to give Bob, her first “investor”, more than he had given her, and the reason is that that was the point when she became insolvent. (She didn’t have enough assets to pay all of her liabilities).

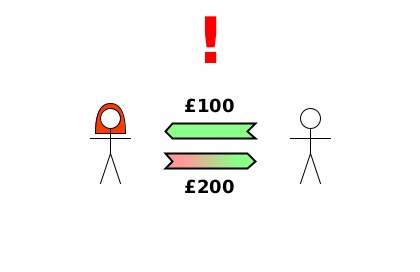

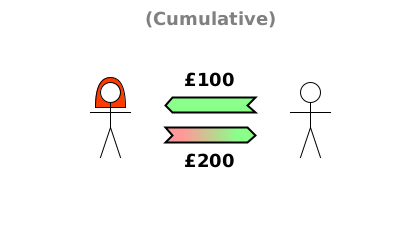

With Bob’s investment, Alice’s RNW increased by £100 (the cash), but also decreased by £200 (Alice’s promise to pay double after a year). Since Alice started with zero RNW, her RNW after the investment was unambiguously negative:

Even though Alice didn’t have to pay Bob anything for a year, she was already insolvent on day 1. Her only asset was £100 of cash, but she owed £200 to Bob. Unless something happened in the following year to increase her RNW, the only way she could pay Bob was by making a promise—which she couldn’t keep—to someone else in exchange for an asset. So someone would end up getting £100 less than they were promised. The only remaining question is who that someone would be.

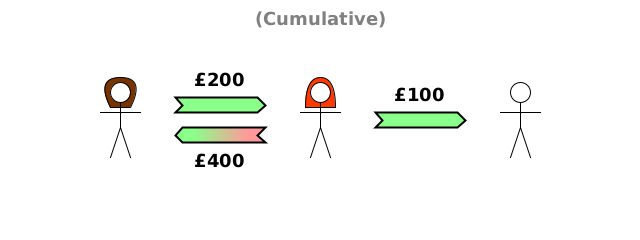

In the example, Bob actually ended up being paid what he was promised because Alice was able to get the cash to pay him from Charlotte when she “invested” £200.

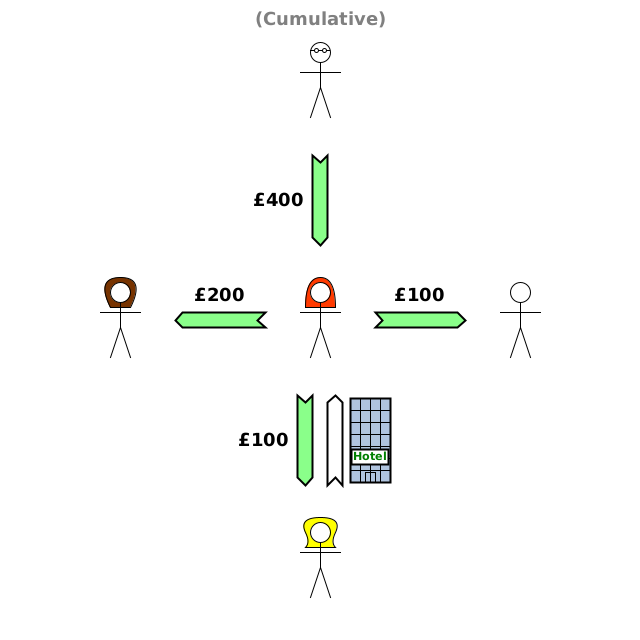

At this point, Alice had £100 of cash, but owed £400. Her RNW was even more negative:

Although she’d managed to put off defaulting by 6 months, she was in a worse situation. She owed £300 more than she had. At this stage, if Alice couldn’t find anyone else to “invest”, Charlotte would lose £300.

Eventually, it turned out that Dom was the one who took the loss, after Alice defaulted. He actually lost £400. We can even see exactly where it went:

Dom’s lost £400 of RNW didn’t disappear: it was just transferred2.

£100 went to Bob (as a return on his “investment”)

£200 went to Charlotte (as a return on her “investment”)

£100 went to Eve (in exchange for allowing Alice to stay at her hotel).

A Ponzi scheme is a form of wealth transfer, from the victim(s) (the final “investors”) to the earlier investors and to whoever is running the scheme.

Conclusion

A Ponzi scheme fails as soon as the first “investor” is promised a return of more than they originally invested, because the scheme becomes instantly insolvent: it doesn’t have enough assets to pay all of its liabilities, and as a Ponzi scheme it has no intention of doing anything to obtain any more assets (without taking on at least as many new liabilities at the same time).

The One Lesson (look at how actions affect everyone’s raw net worth) instantly reveals that a Ponzi scheme is guaranteed to fail. Although it can’t say in advance who will suffer the loss, it can say for certain that someone will.

The reason why limited liability firms have to publish audited accounts is to guard against exactly this sort of problem. If the firm is insolvent, anyone thinking of giving something valuable to it in exchange for an IOU can use the accounts to see that that would be a really bad idea.

Someone who becomes insolvent can get out of insolvency e.g. by producing something, or receiving a gift. Or perhaps if something they own or are owed becomes more desirable for some reason so they can sell it to obtain what they owe. But failing one of these options, at least one of their creditors won’t be paid what they’re owed.

Remember that, apart from production and consumption, economics is a zero-sum game for RNW. Total RNW can only decrease if someone consumes a tangible asset.

I think you mean "Dom’s ... £400 of RNW didn’t disappear: it was just transferred".

The non-disappearance of his "loss of £400" (which still exists) is a tautology. His loss will only "disappear" if he is repaid £400.