This whole substack is about a new approach to economics, summarised in One Lesson:

To understand economics,

look at how each decision or action affects each person’s

raw net worth.

In the introduction, I mentioned that a person’s raw net worth is: what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. But why is it so important?

(TL;DR: it’s what they’d be left with if everyone paid their debts, and it’s the key to making economics as easy to understand as adding and subtracting).

Simple example

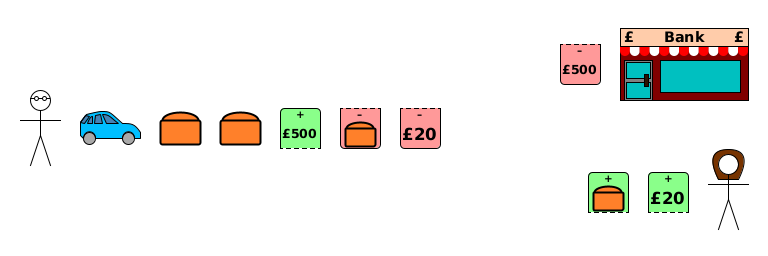

Consider Dom here. He owns a car and 2 loaves of bread. He has £500 in an account at Megabank, which just means that he’s owed £500 by Megabank. As we saw in the Debts post, we can represent this by Dom and Megabank having two halves of a piece of paper. Dom, as the creditor, has the green half, and Megabank, as the debtor, has the pink half. Finally, Dom owes a loaf of bread and £20 to Charlotte, so this time Dom has the pink halves, and Charlotte has the matching green halves.

Here’s a very important question: what would Dom be left with if everyone paid their debts? And the answer is simple. It’s:

what he owns now (the car and 2 loaves)

plus what he’s owed by Megabank (£500)

minus what he owes to Charlotte (1 loaf + £20).

In other words, it’s his raw net worth.

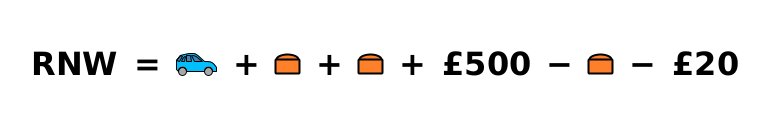

In this case, Dom’s left with: his car + 2 loaves of bread + £500 − a loaf of bread − £20

or to put it more simply: his car + 1 loaf of bread + £480

Pretty simple, I think you’ll agree.

Owing something you don’t have

Sometimes it’s ever so slightly more complicated, because people can owe things which they don't own and aren't owed. This is actually pretty common. Almost everyone who’s had a mortgage has owed more money than they had at the time.

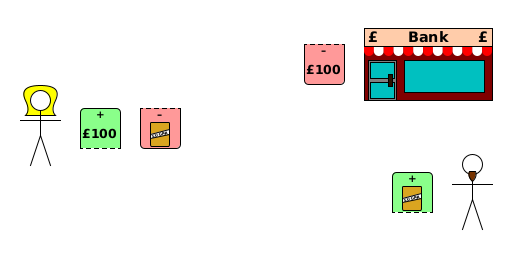

Eve here has £100 in a bank account, but owes her neighbour Frank a bag of sugar.

Her raw net worth is: £100 − a bag of sugar.

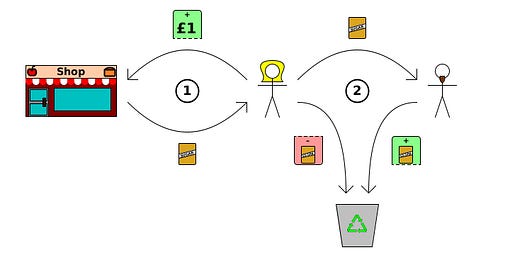

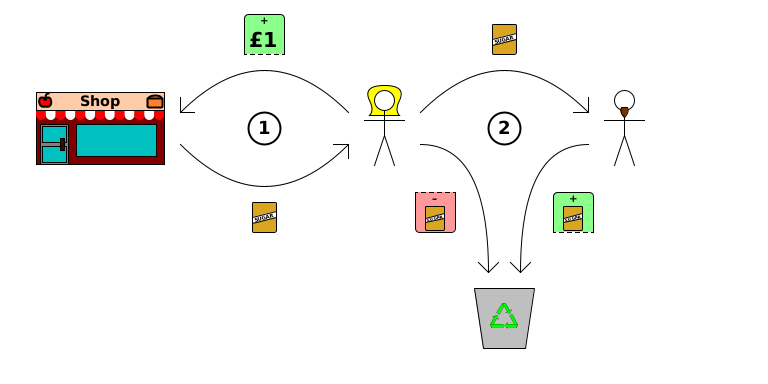

But even though she doesn't have any sugar to give to Frank, it isn't a problem as long as she has something she can swap for the sugar she owes. Suppose the local shop sells bags of sugar for £1 each. In this case, Eve can just:

Buy some sugar from the shop (transferring £1 of her £100), and

Give Frank what she owes him (at which point Frank agrees that the debt’s no longer owed).

(In an upcoming post, I’ll show you how the arrows from the One Lesson logo can make this type of diagram simpler to draw, and easier to follow.)

Let’s look at how everyone’s raw net worth has changed over the scenario:

Shop: + £1 − bag of sugar (gained £1, but no longer has a bag of sugar)

Frank: no change (gained a bag of sugar, but is no longer owed a bag of sugar)

Eve: − £1 + bag of sugar (lost £1, but no longer owes a bag of sugar).

If we add the changes up, we get 0: no change. In fact, if nothing is produced or consumed, changes to raw net worth always add up to 0.

Raw Net Worth makes it easy

You’ll find that looking at everyone’s raw net worth makes it easy to understand what’s going on in almost any situation in economics. Because it’s grounded in the everyday ideas of what people own, are owed and owe, you’re unlikely to go far wrong. Everything which happens either adds something to, or takes something from, a person’s raw net worth; and in almost all cases, it has the exact opposite effect on someone else.

Look at the economy as the production, consumption, and transfers1 of people’s raw net worth, and everything becomes clear.

This includes exchanges, which are just made up of two (or more) transfers.

Shouldn't Dom also have the £20 he borrowed form Charlotte as part of his assets? Even if he's already spent that £20 on something else, that "something" [value = £20] should show in his assets, shouldn't it?