Imagine a baker is working one day, when a vandal throws a stone through the shop window, and runs away. The baker is going to have to buy a replacement for the broken window.

Before we go any further, let’s look at what the One Lesson tells us: how has everyone’s raw net worth changed? And it’s pretty simple. The baker had a tangible asset (the window) and doesn’t have it any more. Nobody else has it either. So this is a type of consumption.

The baker’s RNW has decreased by the window, and nobody else’s RNW has changed. So the whole world’s RNW has decreased by the window. If you’ve never listened to economists, you might think that everyone would agree that destruction is obviously bad.

Good for the economy as a whole?

But some economists actually disagree, saying that, although it is bad for the baker, it’s good for the economy as a whole. They might reason something like this:

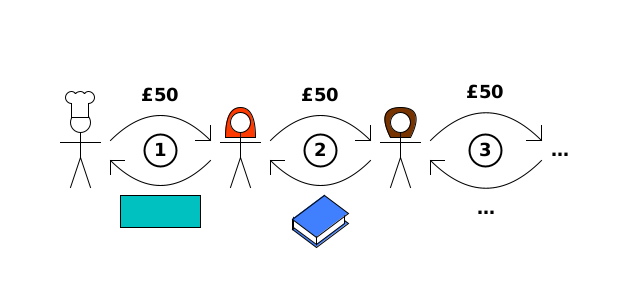

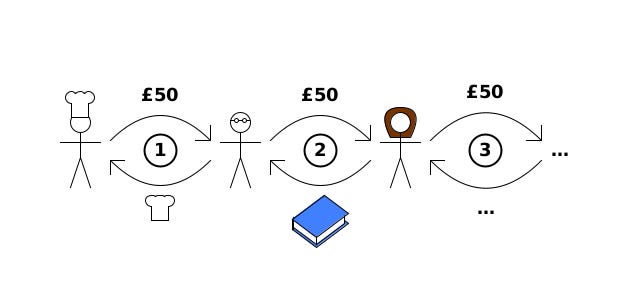

The baker has to buy a new window, which he otherwise wouldn’t have.

This creates employment for the glazier, who now has more money.

The glazier can use this money to buy, say, a book from the bookshop.

This creates employment for the bookshop owner, who now has more money. And so on.

All of this extra economic activity was brought about by the original destruction of the window.

In Economics in One Lesson, Henry Hazlitt used Frédéric Bastiat’s argument1 against this. Essentially:

The baker had to use up some savings to buy the new window.

If he hadn’t had to, he could have used his savings to buy a new hat, creating employment for the hatmaker, who now has more money.

The hatmaker could have used this to buy a book from bookshop. And so on.

In summary, the glazier only gained business at the expense of the hatmaker, and either way the baker lost the original window.

The first group of economists might still argue that the baker would have just saved the money instead of buying a hat, and that forcing the baker to spend by breaking the window really does help to give a boost to the economy.

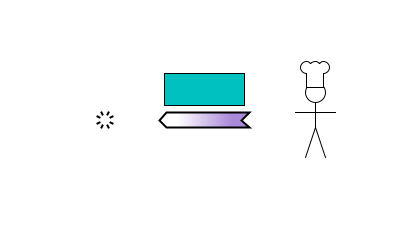

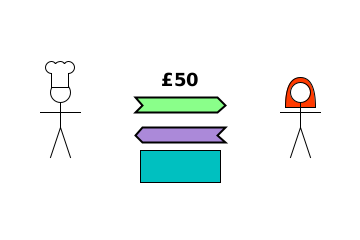

Speculating about what might or might not happen in the future generally leads to fruitless arguments. But the One Lesson gives us a different perspective. Look at what happens when the baker buys a replacement window from the glazier for £50:

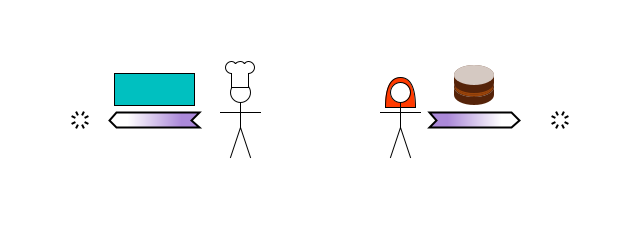

The baker’s RNW decreases by £50 (green tail), and increases by the window (purple tip).

The glazier’s RNW increases by £50 (green tip), and decreases by the window (purple tail).

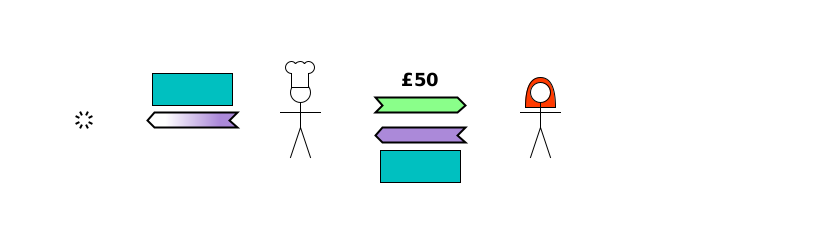

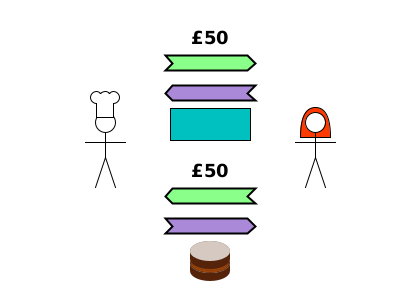

The glazier isn’t simply better off by £50, as some economists seem to think. She’s just swapped one of her stock of windows for the £50, exactly as she was always planning to do. The whole scenario, including the original breaking of the window now looks like this:

The baker’s RNW has decreased by £50. (Gaining and losing a window cancel each other out).

The glazier’s RNW has increased by £50, and decreased by the window.

The whole world’s RNW has still decreased by the window which was broken. This destruction can only be undone by someone producing a new window, not just by selling an existing one.

Economists who believe that destruction is good are therefore basically arguing that it forces more production to occur, and production is good.

But the reason that production is good is that it creates new tangible assets which people can benefit from using and consuming. Wasted consumption, like breaking windows, just forces people to put in the effort (and perhaps expense) of producing a replacement just to restore their RNW to where it started. To conclude that the wasted consumption itself is good is like arguing that because your body’s ability to heal itself is good, it’s therefore good to be punched in the face, because your body will do more healing than it would have otherwise.

More insights from the One Lesson

For some more clarity on how good (or not!) destruction is for the economy, imagine two more scenarios.

First, suppose the vandal throws a stone through the glazier’s window.

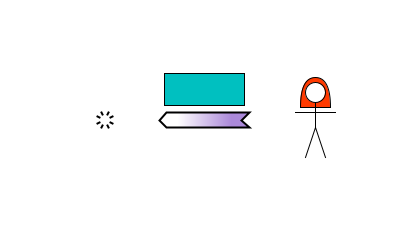

The glazier has to fit a window from her stock. That just leaves her with one less window to sell. As before, the world’s RNW has decreased by the window which was broken. This doesn’t even lead to any extra buying or selling, and it’s hard to imagine anyone arguing that this is a good outcome.

Next, imagine that the vandal breaks the baker’s window, and then throws the glazier’s birthday cake in the bin.

The baker’s RNW decreases by the window, and the glazier’s RNW decreases by the cake. The whole world’s RNW decreases by the window plus the cake. What effect does it have if they spend some of their savings on replacements?

As before, buying replacements is just exchanges of RNW. The world’s RNW has still decreased by the window and the cake, because of the original destruction. The baker and glazier end up with the same money as they started with (because the money just went in one direction and back again), but a reduced stock of tangible assets.

If a theory of economics claims that destruction might be good or bad depending on the trade of the victim, or that two individually-good destructions become bad destruction when they both occur, this should be a huge warning sign that the theory might be flawed.

Is destruction always wrong?

Destruction isn’t necessarily the wrong thing to do. Occasionally things have to be destroyed to obtain a better long-term outcome (e.g. demolishing a decrepit old factory in order to put up a vastly more productive one on the same land). But the destruction itself doesn’t make anyone better off—it’s the production of what replaces it which does that. Any use which was left in whatever was destroyed is lost.

Summary

The One Lesson shows us that destruction reduces the RNW of the owner, and doesn’t affect anyone else’s RNW. We don’t need to speculate about what might happen in the future to see that the world is poorer as a result. The only way to restore the world’s RNW is through production, which uses up scarce time, effort and raw materials. Without the destruction, these could have been applied more constructively to enhance people’s lives. Alternatively, people could have had more leisure time for hobbies, reading substack, or whatever they enjoy doing. Destruction is a path to poverty, not prosperity.

...more leisure time for ...reading substack...

Haha, I like that humorous insert!