Now feels like a good time to summarise what we’ve looked at so far.

People (either real people or corporations) can own things, be owed things, or owe things. If you add what someone owns to what they’re owed and subtract what they owe, you get their raw net worth (RNW). It’s what they’d be left with if everyone paid their debts. And the essence of economics can be expressed in One Lesson:

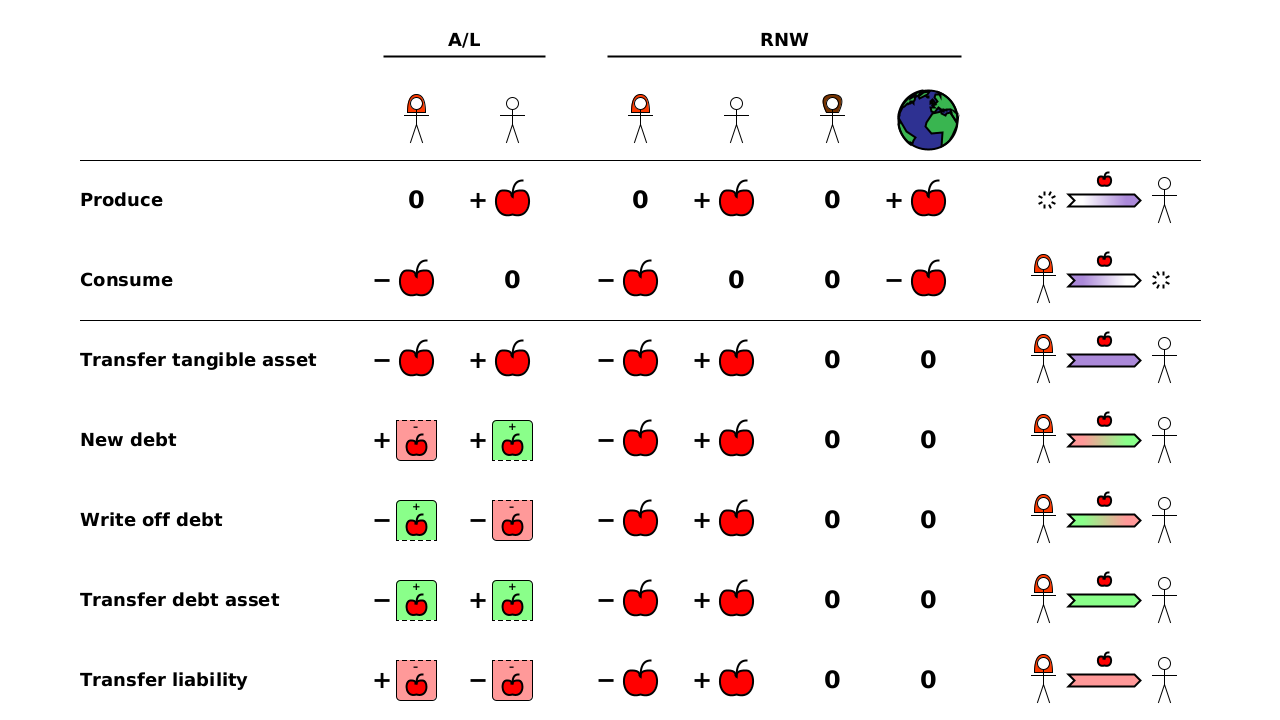

There are 7 types of action1 which affect people’s RNW. Each can be represented with a different colour of arrow: the RNW of the person at the tip of the arrow increases, and the RNW of the person at the base of the arrow decreases. The arrow is labelled with the amount by which each person’s RNW changes. Most arrows have a person at both ends, so the action is transferring some of one person’s RNW to another person: their combined RNW is unchanged. There are just two important exceptions. Production only has someone at the tip: their RNW increases and nobody’s decreases. And consumption only has someone at the base: their RNW decreases and nobody’s increases.

Any economic scenario can be decomposed into a number of these actions, and the effect of the whole scenario is just the sum of the effects of the individual actions. In other words, the One Lesson approach is the economics equivalent of Newton’s theory of motion, or Kirchoff’s laws for electric circuits. This makes it possible to precisely analyse the effects on the whole economy of any scenario, such as breaking a window2.

So the whole economy is just like barter, except that people are producing, transferring and consuming not just goods and services, but also debt assets and liabilities. Or to put it more concisely, they are bartering their RNW.

There is just one complication to this “barter of RNW” story, which the One Lesson makes clear, but most theories of economics ignore: when someone is insolvent (doesn’t have enough assets to pay all of their liabilities), then as things stand, some of their creditors won’t be paid what they were owed, because they can’t be. As a result, these creditors discover that what they thought had been an exchange of RNW was really just a transfer (from them to someone else)3. For anyone familiar with economics already, some of what appeared to be demand was actually not real.

We’ve looked at how barter and money, banking, mortgages, credit cards and Ponzi schemes can be understood by using the One Lesson: looking at the transfers and exchanges of RNW.

If you always imagine an economic scenario as the production, transfer and/or consumption of RNW, and especially if you imagine (or preferably actually draw) the arrow diagrams to represent economic actions, you will find that economics is as straightforward as adding and subtracting different types of thing.

Where next?

I have some thoughts about where to go from here. Here are some ideas:

Look at how firms work, and answer questions such as “Is ‘Profit’ a filthy word” (as suggested by Russell Brand) or “What are the effects of a minimum wage?”.

Consider the financial crisis of 2008, and assess government and central bank policies such as bank bail-outs and quantitative easing.

Examine what can cause business cycles: alternating between periods of high and low economic activity. Also look at whether it is a good idea to try to smooth out business cycles, as some governments have aimed for.

See what we can learn about inflation and deflation, and their impacts.

Let me know in the comments if there’s a particular topic you’d like me to address: either one from the list above or your own suggestion.

Thanks for reading!

Quick summary: breaking a window is bad.

Or a gift which they thought they had received was really nothing at all.